We cross the border to Senegal in the eastern part of the country. Here we have chosen a dirt road which takes us through small communities and beautiful nature that changes from semi-desert to vegetation. We are overwhelmed by the many hospitable and smiling people we meet on our way. People who live in a traditional way and who don't have much - but they have big hearts and strength, which is expressed through their living eyes.

Crossing the Senegal River

We look over to the other side of the river. Just over there is Senegal. Our country number 8 on the journey and once again a huge shift in culture. It's fascinating how getting two stamps in your passport often changes everything. We leave the Arab culture and start in earnest on the Afro-African countries in West Africa.

It's a small border crossing, but it's going well. We cycle through a shopping street with lots of people. Everything from washing powder to small deep-fried bread is sold. We turn down a small sandy side street and at the end of it is the border post. Here we have to stamp out Mauritania. We are shown to the Boss and the bench next to his desk, which is falling apart. A guy comes in and puts a bill in the Boss's pocket. Others come by, another bill in the boss's hand. We also have to drink tea and eat bread while we sit cross-legged on the little bench and wait. After a while, the Boss opens a book in which he makes new lines with a clipper as a ruler. After this, our passport details are neatly written into the book. He was a little strict at first, while his warm side took over, and once he finds out where our names are in the passport, he pronounces them with a funny accent and a smile on his face. He then takes a picture of our passport and sends it on Whatsapp to the main office. The stamp plate is carefully filled with ink and our passport gets an exit stamp with a proper bang. We are officially out of Mauritania.

By the river there are several small boats that constantly sail back and forth with people and goods. We negotiate a price and, together with the bikes, we are placed in a pirogue, which, together with another boat, filled with women in brightly colored clothes, is towed over to the other side. Here we are received by a group of young smiling and very talkative young guys. Contrary to Maiuritania, where many did not want to take pictures, we had barely got off the boat before the young guys said: "Take a picture of me - take a picture of me too" and so it continued until we finally had to say that now we had to check into the country.

We crossed the border with our Mexican cycling friend, Gustavo.

We could feel the shift in culture immediately. There was loud music when we stopped to buy something cold to drink at a kiosk and people in nice, brightly colored clothes. A man in a bright yellow suit, big sunglasses and a woolen hat – a cool funky style that would go right into Vesterbro.

National route 7 – Baobab trees and starry sky

We have chosen National Route 7, which runs from the small town of Ogo to the south to the larger town, Tambacounda. Now that it is a National route, one might well be tempted to think that it is a nice asphalt road. It is not. It is, on the other hand, a dirt road, which turns into a road network of small ruts, before it becomes a dirt road again before Tambacounda. Just the way we like it best.

We are still in the semi-desert, so there are only a few trees and bushes. We are excited to see trees. It is so long ago. We, on the other hand, are not so enthusiastic about the heat. The temperature has taken a leap upwards. Especially in the afternoon, the sun is baking on us, and the thermometer shows plus 45 degrees. Once we hit 50 degrees.

We cycle past a small village and look inside. There are some who see us and wave us in. We pull the bikes into the small collection of houses. In the middle stands a beautiful tree with a huge, dense crown and casts a lovely shadow on the platform built around the tree. It is a Moringa tree which is used to prevent and cure diseases. Marie immediately calls the tree the 'Tree of Life'. In the midst of the scorching afternoon heat, at least it feels that way. We are greeted with curious looks and shown to the platform. We also get a cup of water. Very sweet and thoughtful. The head of the village, the Alkalo, comes and sits down next to us. He speaks French and the local languages Wolof and Pular. We try to communicate as well as we can. We are talking about the family that lives here. Parents, siblings, cousins, who live in the houses around the tree. There are two sandstone houses on either side of the tree. Between them are beautiful mud huts with palm roofs and various outbuildings. All the houses form a circle around the tree, around which the traditional family communities are often built. It is also here that the elderly gather when important topics need to be discussed.

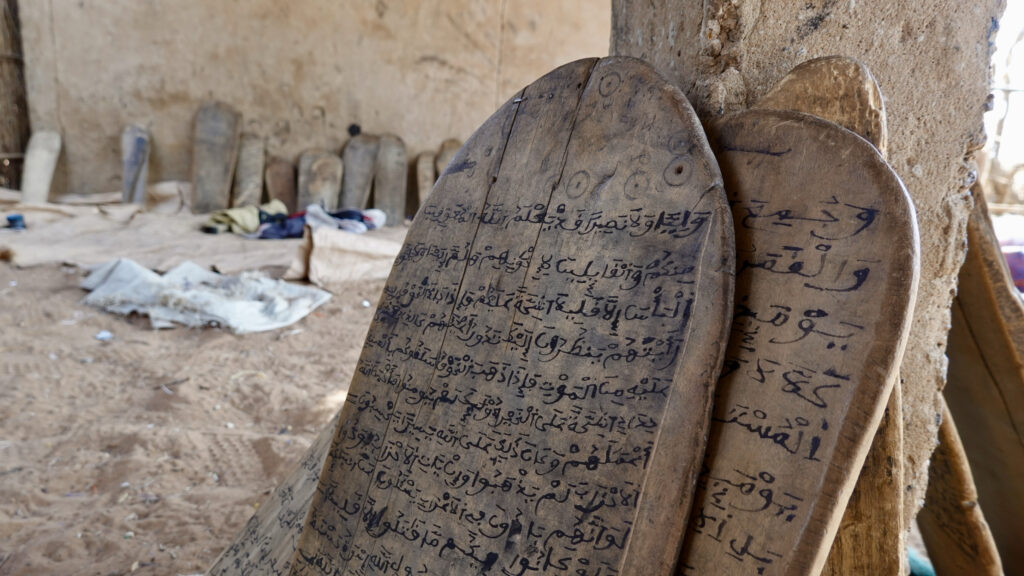

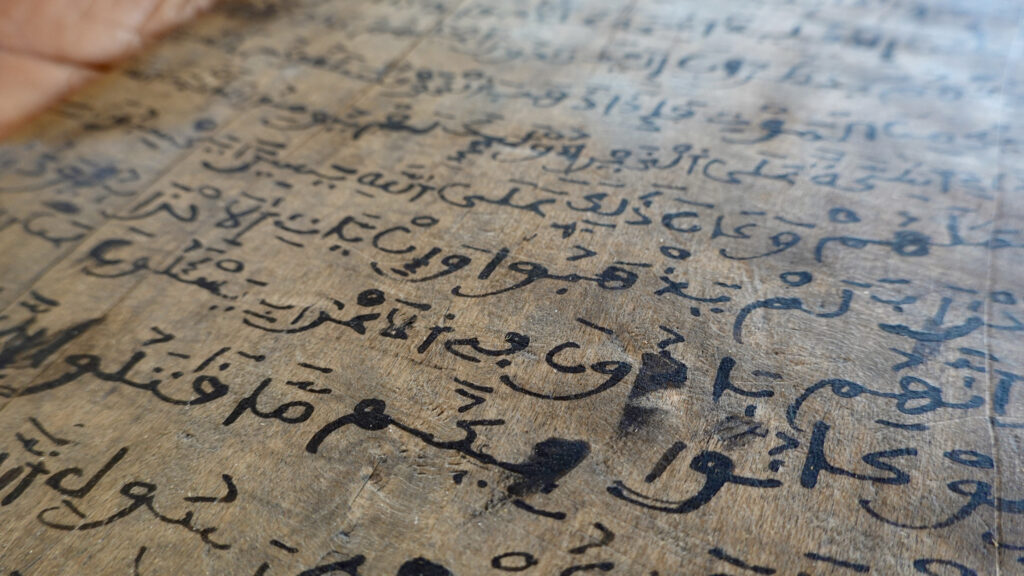

We are shown around and stop at the Koran school, which is four posts with a roof over it. Here we look at the wooden boards that the children write on. They write with a black color and the plates are cleaned with ash and water. It's really smart. We later saw the children are at school and there is strict discipline. It is the older children who teach the younger children, but Alkaloen always has an eye on the school. If there is the slightest problem with the children, they are reprimanded.

We are starting to get the urge to cycle on, but that is out of the question. We must stay to eat. We try to say that it's too much, but it doesn't work. And we also really want to stay and experience more of this fantastic community. Conversely, we are also very careful not to eat their food. We know that this is an area where there is not much to do.

We see how the women are preparing the food. Fresh fish from the river is cleaned. Delicious local vegetables are arranged and cut. Sweet potatoes are mashed together with spices, and the rice is ready to be steamed. The food is cooked in a huge pot over a fire. We quickly decipher that the woman in charge of the cooking has bones in her nose. She cooks for the whole village while managing the children and nursing an infant. While the food is being prepared, we play with the children. There are many, and they look at us curiously. The only "toy" we see is a spare part from a car that a stick can fit through, and then they roll off with it. Another girl has found the remains of a lipstick which she inspects. Otherwise, we see no plastic. No trash. The children help with the cooking and play with each other. When the food is ready, it is carefully divided into several large dishes. The dishes are then distributed. Two large platters for the men who eat under the tree. A dish for the bigger boys and a dish for the smaller boys. The very young children are given porridge and eat themselves, which is an impressive sight. Two dishes for the women who eat in the house. We also get a dish and eat with the men under the tree. The food tastes fantastic. The rice is cooked in some kind of sauce. On top four delicious vegetables and a piece of fish. Young and old sit around the dish, which is on the ground. The fish is peeled apart and distributed so that everyone gets. The same with the vegetables. They sit on the right foot and have the left leg forward. We feel like the stiffest cyclists, who almost can't even sit in the tailor's position for more than five minutes. We are also challenged to eat with our fingers, and we have to practice the technique of making a small ball of food so that it doesn't all go to waste before it gets into the mouth. There is something very special about sitting together and sharing food in this way.

After the meal, the older boys prepare the cart and harness the horse. Here they load all the families' large water cans, which must be filled up. They drive off with approximately 25 cans, and we meet them again at the well as we cycle on. There are many families with their donkeys, horses and water jugs. There are two donkeys who pull a rope to pull the bag of water out of the well. It is a long way down to the water. Really far. The man who is busy filling his cans thinks it's funny if Kenneth and I try to empty the water bag. Are you wondering, it is heavy. The bike arms really get to work. It is hard work to fill so many cans every day. But there is a good atmosphere at the well. It almost feels as if life at the well also serves a social function.

We cycle on, and before we go camping, we see a place where we can draw water. It doesn't take long before we are surrounded by smiling women and men in beautiful clothes. We are welcome to draw water and fill our water bottles. We are very grateful, because water is not a matter of course on this stretch. A boy holds a funny fruit towards us. We understand that we have to taste it. We are standing under the characteristic Baobab tree, which actually has the nickname, the Tree of Life. It looks like it's turning upside down, so it's turning the roots upside down. The trunk is often huge, and the tree can be thousands of years old. It absorbs the water in the rainy season and uses the water in the dry season to make a nutritious fruit. It's absolutely brilliant, as there isn't much other fruit at that time. The fruit is a large capsule that hangs on the tree. It has a hard shell that looks like it is covered in velor. Inside is a dry white fruit with seeds. It has a sour but good taste. You can eat the fruit as it is, use it in cooking, make juice and press the kernels into oil. We get the rest of the fruit with us, and we thank you many times.

We continue cycling along the sandy road and meet only carts pulled by donkeys and horses. No cars. We find a nice spot for the tent and set it up as the sun sets and the moon rises. As we lie in the tent, we talk about the day's experiences. We feel so lucky to be allowed to gain an insight into and be part of their everyday life for a while.

The alkalo and the many women

The next day we cycle past a collection of houses, and when we are outside the entrance a group of women come running towards us. We stop to talk to them. They are super nice and invite us into their village. We thank you. That is why we have cycled away. To experience and learn about the lives of the locals. We enter a collection of houses. The fire is going, and the women are busy with various household chores. Everything stops when they see us and they curiously come over to say hello. There is something completely magical about the immediacy and openness with which we often meet. We are seated on a covered terrace made of wood with a roof of palm leaves. We talk together as best we can. They in the local language Pular, and we in English spiced with sign language. The mood is good. There are smiles and giggles. The women are dressed in the most beautiful colorful clothes and the scarf smartly tied on their heads. They are very sharp, and we wonder how they can keep their clothes so clean and neat when the ground is dusty and they live in small mud huts. We look down on ourselves and our dusty, boring cycling clothes by comparison. Their lips are painted blue and they have two markings next to the eye. They get that as a child to show which family they belong to. The women surprise us with food. It looks like some kind of grain, but it's millet, which they pound with a stick in a big wood-killer standing on the ground. There is also a cup of milk to be mixed with the millet. It is meant to be eaten with the hands. Marie gives it a try, but we surrender to our spoon, which we have on the bike. It tastes good, and we thank you many times.

On the terrace next to it, Alkaloen sits in front of his hut. He is older, smiling and looks very friendly. We talk to him, but it is difficult in the local language. Before we are allowed to cycle further, we must rest. We try to say that we want to leave, but we can feel that this is how it will be. So we lie on the terrace in the shade and listen to life in the village. Millet is being pounded, a cow is chewing the cud, the goats are frolicking, the children are playing and all of a sudden the woman scolds the donkey, who has tipped the lid off a large tub of millet and is now munching away. Before we cycle on, we ask if we can take pictures of them. We always ask and are always very attentive to whether it is ok. There is no doubt that women think it is ok. They laugh lovingly when we show them the pictures afterwards and everyone wants to have their picture taken. A mother also wants her baby photographed, but the baby is not ready for that, and it screams at the top of its lungs.

One of the women points to the child, and we understand that she is asking if we have anything for the child. So we ask if we can pay for the food in order to give something back. The women refer to the Alkalo, who decides, and he rejects it kindly but very firmly. There are so many codes and we do our best to get it right. After a long farewell ceremony, we cycle on with a big smile. What amazing women and personalities. We are talking about the fact that there was only one man and several women in the village. The man was definitely the Alkalo, the head of the family. Marie prefers to believe that the other men work in the fields. Kenneth is more inclined to polygamy, which is quite normal in these parts. It is in each case a possibility if we look at the interaction between the Alkaloen and the women and how the place is built. The Alkaloen has its own hut, and so do the women, and then the women take turns sleeping at the Alkaloen. It's legal and completely normal here, but the Alkalo was older and some of the women were young, so our brains with a different world view have to chew on that a bit.

In the evening we reach a small village again, and here we are also invited in. They ask us if we want to sleep there, and of course we would very much like to. We are placed on a wooden platform raised from the ground with four legs. Right next to the small road that goes through the town. Then we can follow what is happening in the city and the residents can also follow what we are doing. It's absolutely perfect.

It's a really good evening with good talks as best we can in a mix of languages and once again wonderful food. Marie sits on a bench with the women. They think that the zipper in the pocket of the pants is fun and a sports bra is absolutely fantastic. Marie, on the other hand, is fascinated by their beautiful, colorful dresses and lots of jewellery. As darkness falls, two teenagers sit down on a bench at the end of the plateau. Marie watches and says: "Ahhh TikTok". They laugh and say that Marie speaks their local language, Pular. It's a wild contrast to the rest of the experience. The women and girls are dressed in the beautiful traditional dresses, the food is cooked over a fire and the water is fetched from the town's well outside the town. They sleep in beautiful but primitive mud huts. The donkeys and goats walk the streets. There is no electricity, but there is a fire and light from the moon and the grocer has a flashlight. And then the young guys (we didn't see any young women) are on social media. They are the only ones we have seen using phones other than push-button cell phones while we have been in the small village. The contrasts are great, and it is fascinating and fantastic at the same time that we think about what access to the internet and social media will do to traditional society and the generations in between. Will it affect development positively, or will it create gaps between the generations.

The world is changing and inspiring

The route is only approx. 300km., and it takes us four days to cycle the distance because we are invited in so many times. The hospitality is immense and we enjoy being allowed to be part of these communities and experience how they live. A way of life that is so different from Danish society. We have shaken so many hands when we cycle through the villages - children and adults. Got so many smiles and gave the same in return. A life energy radiates from the eyes of most people, and they have an openness that is quite special. We can already feel how the energy and togetherness is much more intense here in Afro-West Africa, compared to the Arab countries we have just come from, and especially Denmark, where everyone has a much larger private sphere. Most people on this stretch don't have much, but they can get by. Yet they share with us and we are included in the community immediately. It only happened in one town that the children asked for gifts. Otherwise, we will be told kindly, but very firmly, that we have to pay for the food. It's a difficult balance, because we really want to give something, especially because we know it's a poor area, but conversely we also have to respect and accept their kindness and traditions. We have been given a lot of time to talk about what the good life is. What does it take? Is it our modern life with lots of materialism or can less do as well? Where is the limit for what is needed? Here everyone has a place and a task in society and must help to make society function. And how will these communities develop in the future when the 'TikTok' generation takes over. We talked at a small trading post with a guy who could speak English. He had gone to school in a bigger city for four years. He had returned home to his family because this was where he belonged. It is a good development, but we also hear about more people who want to come to Europe. What will the living conditions be like in the area going forward. Will there continue to be water in the wells which are already very deep to get water. It is clear to see that there is a big difference in the small communities depending on who is Alkalo. He is often older and sets a direction and a mood for society. We hope that they find their way in the development and maintenance of their culture and traditions.