It will be a harsh tale about the most dangerous country on our route. Nigeria is known for kidnappings, murders, ritual use of human body parts and overall a security situation that is completely wild and hopeless.

I promise it will end happily though. Very happy even.

But I must warn that what follows is very rough reading.

Two young men face each other shirtless. They move slowly around in circles, as if in a slow-motion dance. One looks significantly more tired than the other. Around them stands a group of young men. They watch silently. And then – suddenly – one man hammers his bare fist into the other's face.

I see it happen in a fleeting glimpse as I cycle past. I immediately look away. Afraid that attention will shift to my presence. With my mind full of troubled thoughts, I wander further down the dirt road, between the small houses. I have only been in Nigeria for a few hours. I have reached the big city of Lagos and wanted to take a short cut of smaller roads to avoid the heavy traffic and am immediately confronted with the harsh reality. A fist fight in the street. I have no idea if they were fighting for money or for honor. But regardless, it was a disturbing experience, as an introduction to the big city, and to the country.

That evening, sitting safely in my hotel room, I read the news on the Nigerian online newspaper. 10 people have been arrested today. They have been caught selling body parts from people they have killed. The body parts are sold to "traditional healers" who use them for "ritual purposes". The prices are mentioned for different body parts. Fresh body parts are more expensive than old body parts that have been dug up in the cemetery. A fresh head costs about DKK 500.

Welcome to Nigeria.

My brain hurts

I have cycled straight to Lagos to sort out my head, which is hurting more and more. My brain feels swollen. My appetite has disappeared. My mood is at an all-time low. I'm a little scared of what's wrong. When I search the web, the symptoms point to a possible brain tumor. Suddenly I feel very alone.

Fortunately, I have contact with the Danish consulate and some business people in Lagos, who are a huge support and they wrap me in care and check up on me.

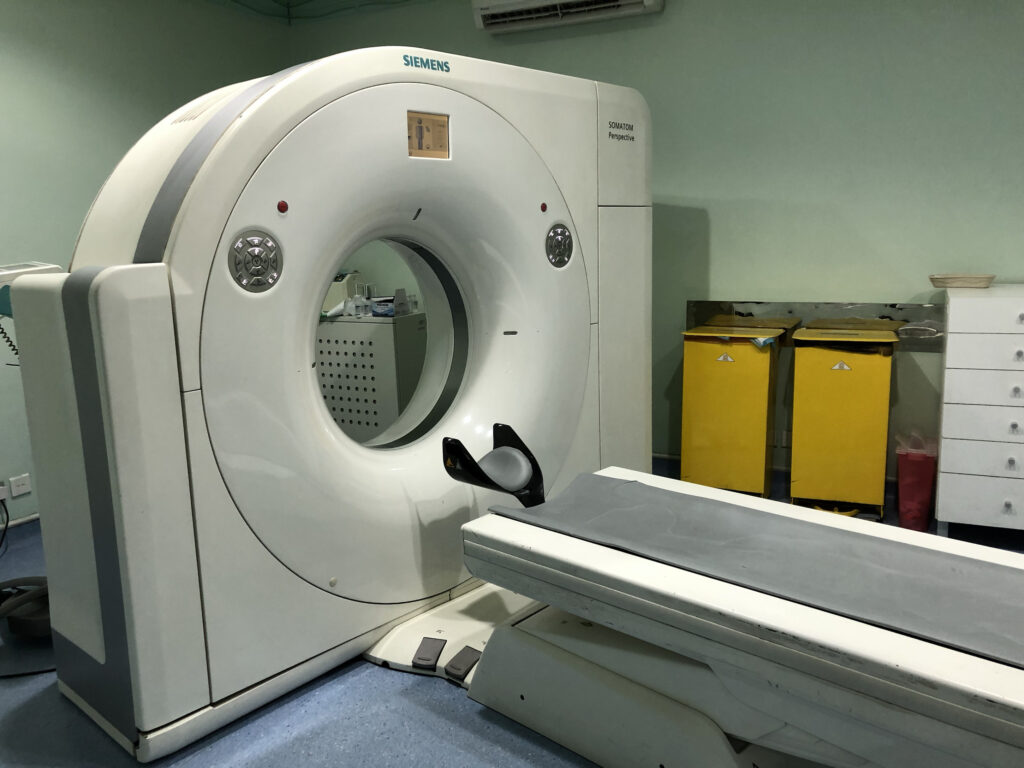

I cross all plans off the calendar and go to the hospital the next morning. Here I am checked by the doctor and have a CT scan of the brain carried out. The doctor can see an infection in the ear. I don't really believe that this is what causes such big problems. But he says he sees it often because the air is so polluted and at the same time it's so hot and humid. Lagos is one of the most polluted places in the world. And as the doctor says, there are faeces and corpses swimming around in the rivers in the middle of the city.

Later that evening I am informed that the CT scan does not immediately show any problems. At the same time, I see on social media that Emil Erichsen has just interrupted his circumnavigation and has gone home to Denmark, to be operated on, for the same problem as me.

Rest and vitamins

I meet some real angels who put me up in a luxury hotel so I can get to the hooks, eat nutritious food and relax. I will always remember and greatly appreciate that help. I really needed care at that time. Especially because the insurance company's crisis response completely failed me. Even to such an extent that I have submitted a complaint about the process.

Rest, better diet, vitamins and care help as they should and within 3-4 days I can feel an improvement. I consult the doctor again and he can see that the infection has subsided, but says I will be able to feel it for a long time. But there is nothing in the brain to be concerned about.

Together we decide that it is safe for me to continue cycling.

Angels of Lagos

Although I didn't get to do any of the things I wanted to experience in Lagos, I still had a great few days getting to the hooks. I met several times with Jette, Denmark's consul general, who is a fantastic woman. I also met Sanne, who works at the consulate and has lived and worked for the last 40 years in Africa. It was really exciting conversations with the two, about Nigeria and Africa.

I also had the great pleasure of meeting Arla, which is present in Nigeria. In addition to being fantastically inspiring people, they talked about how they collaborate with the state to build up a dairy farm in northern Nigeria. Unlike pure relief, this project has a clear commercial aim, which in my eyes immediately makes it far more sustainable for Nigeria, because you activate other industries and together you build a meaningful business. In other words, through the purpose of making money, knowledge is passed on to locals. Just as you activate other industries that can supply spare parts, feed, etc., etc., for the operation of the farm.

It is a really exciting project, which I very much hope can help shape the direction for a new way Denmark can be present in Africa.

Off on the bike – out into reality

Marie has chosen to stay at home with her family in Denmark a little longer, so we agree to meet in Yaounde in Cameroon instead. This means that I am cycling alone through Nigeria.

First day on the bike, out of Lagos, spirits are high. Many people greet, wave and smile. It feels like being in a bike race where all the people are cheering me on. When I stop to eat, people come up and ask me. Everyone says welcome. Many want to take selfies with me. I clearly feel a great joy that I am visiting their country.

I'm just about to jump on one of the misconceptions I've been very careful to avoid from the start: Even though a lot of people are nice, that doesn't mean bad things don't happen.

That same evening, I open the newspaper and read two stories:

On Friday, seven men with AK47 rifles step out onto the road and shoot around. They kill one person and abduct seven random people. Later, they release two hostages, but keep the remaining five, to demand a ransom. Now here, a week later, the police are still looking for them.

I'm sitting in a hotel less than 50km from where it happened. The road on which it happened, I had intended to cycle on tomorrow.

The second article is about a murder of a young girl. Three men have been arrested in the case. It is a mastermind aged 27 who ordered a kidnapping of the girl, as well as two young men aged 22 and 23 who were to carry out the kidnapping itself. But the girl resisted, and the situation ended unhappily with the kidnappers strangling her. It happened about 100km from where I sit and read the story.

Suddenly I feel the ground burning beneath me.

I closely study the map and my route again. I am considering alternative options. Thinks through the background of kidnappings in the area. I end up adjusting the route through Enugu state a bit, to some smaller roads.

It would take a huge amount of bad luck for me to end up in a random kidnapping on a country road, which is the most likely way I could be caught. The other possibility is that someone who is already in connection with a kidnapping network spots me, follows me, or possibly discovers where I am staying in a hotel, after which they target me. But then they have to think and act quickly, because I move quite a lot every day.

Most kidnappings are select targets where the capture is planned. In other words, time has been spent before that happens. And that time works for me. Because before they get it planned, I'll be gone again.

In other words: Yes – it is dangerous here in Nigeria. But my assessment is that the risk of me getting into trouble is very, very small.

Specifically about kidnapping

Even while we were planning the trip at home in Denmark, we were aware of the risk of traveling in Nigeria. But through hours of research, I have gained a much more nuanced picture of how the kidnappings take place and why.

More than 2,000 kidnappings occur annually in Nigeria, with a total number of victims of approximately 6,000. The kidnappings happen almost exclusively with the aim of demanding a ransom. The northern states account for the vast majority of cases, primarily driven by the Islamist terrorist group Boko Haram. In the southern states, a number of kidnappings also take place, here it is primarily expats who are the target, because the kidnappers expect large ransoms.

In the intermediate states, kidnappings also take place, but to a much lesser extent. Here, it is mainly random attacks on the country roads, where the victims are taken out of their cars. As well as planned kidnappings, targeting well-to-do locals.

Nigeria is 924,000 square meters and has 225 million inhabitants. This means that the area is more than 20 times larger than Denmark, and the population almost 40 times larger.

So if we boil down to Danish conditions, the 2,000 kidnappings correspond to approximately 50 kidnapping cases annually in Denmark, with 150 abductees.

I can't find any reports of tourist kidnappings. But as a wise man says: "That's because there are no tourists in Nigeria!". And so anyway. Because I am in contact with other cyclists and overlanders who travel through the country. I am fully aware that because I know 20 travelers who have not been kidnapped, that is not a basis for statistics. But I have spoken to several of them about how they experienced the security situation. And that reassured me.

In addition to a more concrete research of the country, which the Ministry of Foreign Affairs advises against traveling to, I take various precautions. I don't talk to people about where exactly I'm going, so as not to make it possible to plan a kidnapping. The exception to this is when I talk to the police at the many checkpoints, where I sometimes discuss my route with them to see if they consider it safe. All the times I have spoken to the police they have assessed my route to be safe. I cycle in my tattered clothes, I don't wear a watch, I hide my electronics so I don't immediately radiate money. But I am also fully aware that no matter how much I look like a vagabond, the white man is a rich man, in everyone's eyes. Which is also an indisputable truth.

And I don't drive with headphones, so I'm always very aware of what's happening around me.

Last but not least, I had a thorough conversation with an acquaintance who works professionally with hostage-taking, and through him gained a deeper insight into what happens if the accident were to happen, and what precautions I can take in that direction.

The newspaper vs reality

Through the work I had done in laying out a route that goes through some of the most peaceful areas, I felt relatively safe. But I have to admit that I was still quite affected by the extremely harsh reality in Nigeria.

One evening I read in the newspaper that a 3-year-old boy had been abducted and had his penis cut off because it was to be used in a ritual. The two abductors had visited a "Ritualist" because they wanted to be protected from "all weapons and all ammunition". The ritual also included the rape of a 13-year-old girl. I started crying when I read it in the newspaper.

It was a completely crazy ambivalent feeling to be in the country. Every day, when I sat on my bike, I received the warmest welcomes everywhere. People paid for meals, sodas, mangoes. People shook my hand and their innocent eyes shone with warmth and hospitality as they welcomed me to their country.

But every afternoon I locked myself in a hotel, separated from hospitality by a locked door. Here, alone in a wretched hotel room, I opened the newspaper every night to find out. And then it was a completely different picture of Nigeria that I was presented with. Raw violence, deception, chaos and corruption. Much of it happened far too close to me.

I rode up and down a roller coaster of emotions, torn between hospitality and fear that something would happen to me.

If I had cycled across the country without opening a newspaper, without researching beforehand, without understanding the security situation, it would have been a much cooler experience. Instead, I would have clear memories of a people who are proud to be Nigerians, a people who are happy, welcoming, hospitable.

It all comes a little too close

Enugu, about halfway through the country, was the worst of the 8 states I cycled through.

Here I read one evening that 2 policemen had been shot at a checkpoint, 6km from where I was sitting. The next day I had to cycle through that checkpoint! I made a small detour. A total of 7 policemen were shot last week in Enugu.

The next morning I quickly cycled out of town. Once out in the country I felt safer. A herd of cows came walking towards me. They filled the entire road, so I pulled all the way to the side and stopped. Let them pass. The first two cattle drivers didn't even look at me when I said hello. The two in the back carried rifles over their shoulders. The stomach twisted. I started the bike while saying good morning to the men. One stared at me. Without saying anything, without taking his eyes off me, he made a hand gesture that means "where are you going?". I replied “Nsukka”. He made the same hand gesture again while maintaining his unfriendly gaze. I answered again, revving the bike up and turning my back on them. My heart was beating a little harder than usual. Here in Enugu, one of the big problems is conflicts between people who drive their cows around the countryside and the farmers who are tired of the cows eating their crops. It often leads to violent conflicts and murder. Deep down I knew that I am not part of that conflict, but I also knew that the cattle drivers have a reputation for being generally criminal and they have carried out kidnappings in the past.

Enugu was a wild experience. Not just because of the higher crime rate here, compared to the other states I had to go through. But also because people were very intense. There is a lot of temperament that is given free rein. People are extremely loud. Tendency aggressive. Everyone is nice enough to me, but the atmosphere is wild. Not pleasant and welcoming, but confrontational. Not bad confrontational, but confrontational nonetheless.

Here, for example, I don't dare to take pictures because I'm afraid that people will get mad about it. And I don't want to put myself in a bad situation that is difficult to get out of.

In comparison, I saw how two people got out of their cars and shouted at each other, in traffic. One had blocked the way for the other. Within 30 seconds there was a mass fight between 20 young men who chased each other around between the cars.

The shoulders fall into place

When I cycled into Benue state I could feel that people were more relaxed and my own shoulders automatically fell down too.

There were still really many checkpoints. I cycle through 20-30 pieces a day. Several different forces man the checkpoints. It can be local police, federal police, the military, local security guards or the migration authorities. Most of the time I can just smile, wave and drive straight through. A few times I was stopped, but only 2-3 times have I been asked for money, which I could easily say no to. But corruption at checkpoints is huge in Nigeria. It is difficult to find an exact figure, but many, many millions are paid at checkpoints to the police. I see it all day long, small notes being handed out of the car window to the officers. There is normal practice. Fortunately, there has recently been a case where some police officers were fired after a tourist filmed an extortion and put it on YouTube. Several times I could sense superiors in the background of a checkpoint ordering junior officers not to ask me for money.

But usually the guards stop me simply because they want to chat and hear what kind of rare fish I am. Or take a selfie with me.

The joy is overshadowed

There are so many great stories I would like to tell from Nigeria.

I've taken, I don't know how many selfies with young people who stop me on the street. A couple of times I experienced someone riding after me on a motorbike and saying: “You didn't stop when I called you. But can I take a selfie with you?”. And of course everyone has to. Incidentally, it's funny to think that I must have a trail of selfies with locals after me, on social media.

I also love the way people greet me. Firstly, it is usually with a handshake which has several "settings" and ends with a small snap together. At the same time they ask “How are you sir? How is the day? How is work? How is the weather? How is your family?”.

And I would like to talk about the different tribes I have met, who can be distinguished from each other by the different cuts they get on their faces as children, which tell which clan they belong to.

At the same time, there is also so much I would have liked to have experienced, things I would have seen and done.

But the security situation overshadowed the joy of being here. And that is the country's problem, also in a larger context.

They find it difficult to attract investment due to security. Furthermore, corruption is huge and just as much of a hindrance to sensible development and foreign investment.

It is clear that the large oil production that the country has been responsible for for many, many years has brought great wealth into the country. But it is equally clear that that wealth has not benefited ordinary people at all.

The country is full of corrupt and bad leaders. It prevents education, upskilling of labor, development of a better business foundation, etc., etc.

Again we must ask ourselves in the West why we continue to support such a rotten system which enriches such bad leaders and keeps so many people in poverty? The answer is quite simple: Because this is how we ourselves make the most money from Africa.

The hidden killer

The last days in Nigeria, I cycle through the state of Taraba. I am approaching the beautiful mountains in the east. There will be fewer people. People live in small huts in the countryside. The farms are neatly laid out, with well-tended fields. The cattle drivers greet me. The mood is good.

I have to drive a climb of about 1,000 meters in altitude, on a half-bad road. It's not unusual for me and I don't put anything special into it. But it will quickly turn out to be a completely surreal day.

First I meet a truck where two rear tires are torn to pieces. The driver takes it very calmly and says that he has sent his mate off to buy new tyres.

2 turns further up the mountain, a young military man on a motorcycle pulls up next to me and asks if I can help him. He has crashed on the motorbike and has got deep wounds on his ankle and elbow, as well as a lot of skin abrasions all over his side. We stop and I find the first aid kit. I clean his wounds and bandage him while telling him to go to the hospital and get it done properly. He says yes - but I can tell by his look that he is not coming to the hospital. I give him my last remedies to clean and care for the wound, as well as antibiotic cream. He is very grateful. He says he will wait for me at the checkpoint at the top.

A few more turns further up I see a white spot on the mountainside. When I get a little closer, I can see that it is a minibus, which is in some bushes. I stop and take a picture. As I stand there, the realities slowly dawn on me. I can see people carrying things from the bus up the road. It must have just happened. The bus has overturned 10m from the road. I hurry to drive under the bus, where there is a group of people. I ask what happened. A woman tells me they had an accident, 3 people have died. Several people have been injured, one of whom is badly injured and has broken bones. I ask if I can help, but they say they have sent someone for an ambulance. At the same time, another minibus arrives and I ask if he can take some of the wounded with him. He says they will probably take care of it. I don't want to stand and stare at other people's misfortune, so when I get confirmation again that they don't need help, I drive on. As I cycle off, I drive right past the three dead bodies, as well as the woman who is badly injured, who is lying close to the road. I get a huge lump in my throat and am deeply affected.

When I reach where the bus has gone over the edge, several injured women are sitting on the side of the road. Some men are still carrying large sacks from the car wreck, up the slope.

I stop and ask if everyone is ok and say I'm sorry for what happened. They say they are waiting for a car to take them away.

A few more turns further on, I can't believe my eyes when I see another wrecked minibus. It is in the middle of the road, upside down. All the windows are broken and the roof is pressed together. About 15 women sit in the shade under a tree. I ask if everyone is ok, and breathe a sigh of relief when they say they are. But they are waiting for someone to send them a new car so they can get out of there.

As I cycle the last stretch towards the top, my head buzzes with the accidents. How tragic to experience. At the same time, I must also admit that I have slowly got used to the reality in West Africa. But now, with this shock, I see again what is actually happening before my eyes, every day on the roads. Anything that can move on the road is consistently overloaded. People sit on the roof, on the radiator, on the back with their feet in the trunk of the cars. The buses are jam-packed with people, while the luggage compartment is wide open and the luggage is lashed down, one and a half meters behind the bodywork. People who ride motorcycles often sit on top of the tank because the back seat is completely packed with things. Or you sit 3-4 people on a motorcycle. Often with the fourth man across the tank. I also see one or two goats, tied around the belly of the driver. Chickens hanging from the handlebars.

At the same time, the roads are often very damaged and people drive slalom between potholes and large stones. The traffic rules are completely out of play. The drivers are incredibly bad at assessing consequences, and dangerous situations arise again and again because all the people only look straight ahead and never brake.

But the miserable conditions and lack of skills and training of drivers are not the worst. I find it really tragic to see so little respect for one's own life and that of others. It is absolutely crazy to experience that you simply consider it a natural part of life, that the traffic is so catastrophic.

There is a lot of talk about kidnappings in Nigeria, but the reality is that traffic poses a far greater risk.

When I had almost reached the top of the mountain, a red Toyota Corolla came rumbling past me. The trunk was open. Inside the trunk were two of the injured, elderly women from the first bus accident. A young man was crouching on the bumper, holding onto the boot lid as he swayed menacingly back and forth as the car avoided the potholes in the road.

At the checkpoint at the top, the young military man was indeed waiting for me. He was still very grateful and gave me a box of tea, from the local tea plantation, across the road. His mother came running across the road and wanted to greet me. It was very touching. He was a really good and caring guy, but even so, or maybe just because of that, I couldn't shake the thought that with my last first aid kit in a bag on the handlebars, he had driven straight past all the women who needed help, without to stop.

The meeting with Sali

In the afternoon I reached the small village of Maidan. Here I was supposed to meet Sali, with whom another cyclist had put me in contact.

Sali got me lodged in my own room, heated water so I could take a hot bath and fed me. We spent the afternoon with his friends, who had come to watch the Premier League final, on the only television in town. Suddenly I had ended up in a cozy community with the nicest people.

After the match we talked about politics and the situation in Nigeria. And they were very curious about Denmark.

I was tired and full of experiences, so when the clock approached 9 pm I retired to sleep. Before I went to bed, Sali invited me to join the village's morning gathering. It required getting up at 5 in order to be in the common house at half past six. But of course I said yes.

The strength of the community

As we walked up to the community hall in the first faint morning light, we heard singing through the open door. Around 30-40 of the village's residents had already gathered inside. They stood in a circle holding hands while singing loud and clear. We joined the circle. The song was incredibly beautiful. I sensed that it was a compliment, because I could recognize a few phrases from the Muslim greetings I know. The song was not like we know it at home, where everyone sings in chorus. It was polyphonic. Three of the women sang different lead voices. The rest sang several different underlying voices. It was so beautiful that I already got a lump in my throat.

When the song ended, we sat down on chairs along the walls. Blankets were spread out on the floor in the middle and some of the children, as well as some of the mothers, sat there. Some of the children babbled a little, but no one shushed them. They were allowed to be who they are. Children.

The village chief began to speak. Sali had told me that there would be a "discussion" where you could say something that would be heard by the village. A question, or a thought, or an idea.

They translated for me so that I could understand that everyone welcomed me and told me that they were happy about my visit. Formal but heartfelt words were used and I was again touched by the great hospitality.

When he was silent, I was encouraged to speak to the villagers. But I have to admit that the lump in my throat would not go away. I had tears in my eyes and was so affected by the completely surprising strong cohesion and community I met here. I knew everything I wanted to say, but couldn't get it past the lump in my throat, so it turned into a very emotional and very short thank you.

During the rest of the discussion, where several different people had something to say, there was complete silence and everyone listened to what was said. 80 people were gathered, all with respect for the speaker. No one answered back or interrupted. One burped loudly a couple of times, but it certainly wasn't an insult, just some air that needed to get out.

Sali took the floor and I could sense he was starting to talk about me. He mentioned countries and cities I've been to. So even though I didn't understand what he said in Pular, I knew the gist of it. People found it exciting and moved forward on their chairs. There were smiles and nods and small outbursts lifted the mood.

After Sali was silent, I asked if I could speak again and tell why I was so moved.

In the Western world we are becoming more and more individualized. We have to perform individually and we are measured and weighed on that. At the same time, it has been a long time since Marie went home to Denmark and I have been alone a lot. Like the security situation in Nigeria has affected me a lot. So when I walked into such a beautiful space this morning, with such a strong community, I was completely blown away. It immediately made me think about my own life. About what is important and about how we as humans are not only dependent on each other, but also strengthen each other. The most beautiful things in life happen when we are with others.

We all stood up. The head of the village prayed for all of us and specifically for me, that I may have a safe journey and many good experiences yet, with many other people on my way.

Then I was encouraged to pray. Fortunately, they said I could do it in Danish, so I did. And then we sang again. Just as beautiful as before.

Imagine if every day in Denmark started so beautifully.

Outside the communal house, almost all the residents came over and shook hands, looked me kindly in the eyes and said: "You are welcome!".

I could not imagine a more beautiful end to the journey through Nigeria.

Sali said to me:

"Only by showing our love to other people do we have a right to ourselves".

But he is also a trained theologian, as it turned out later. I still took his words to heart as the best memory of Nigeria.