Everything is new.

Language, gestures, manners, sounds, smells, customs and everything else were reset in the hour ferry ride it took us to change continents.

We arrived in Tangier. A metropolis with a history that has stretched in many directions. From Arab stronghold to divided international zone under Spanish and French colonial rule. Before that, it was the fringe area of the Berbers. And most recently a beatnik town with a colorful population of odd existences that ended up in decay.

Today it is a city with ambitions to rise again, as a destination worth visiting for tourists. The city is not without charm, but perhaps there is still a long way to go to fulfill the ambitions.

We walk through the small streets of the small Medina. A lot is sold that no one needs. But when we spot an elderly man in a tiny stall, our hands find their way to the banknotes in his pocket. The man sells French nougat. Or more precisely, he sells Moroccan nougat. We have been in Africa for less than three hours when we experience the first taste explosion. The nougat is light brown and chewy, but firm enough to be cut into blocks. It has a delicious deep flavor of nuts from a sunny valley, in a warm country. We are completely sold and buy a huge bag of 1/4 kg for 50 dirhams (35 kr).

Around us are small cafes, and we sit down and observe the city life. There is something very exciting about arriving in another world. All senses are wide open. All impressions are absorbed, enjoyed and processed. Sometimes with astonishment as a result, often with excitement at learning something new about the world and the people who live in it.

We have decided to spend a single night in Tangier before jumping on the bikes. We try to navigate prices for everything, including the hotel room, where we pay 250 dirhams (175 kr) for something that could be included in Nul Stjerner. It was my first experience that some things in Morocco are disproportionately expensive, while other things are significantly cheaper. For example, a delicious freshly baked large round flatbread costs 2dh (1.5kr).

The afternoon in Tangier became almost a foodie tour in the small streets and stalls, where we ate and drank our way through the city. Cakes, nuts, olives, coffee, tea, freshly squeezed juice and finally a Tajine for dinner. We accidentally hit a small place that didn't look like much. It looked more like a barbecue bar. But even here they made a beautiful tajine, which is a small clay plate on which a dish of potatoes, meat and vegetables is simmering, under a clay top. It is served bubbling hot. It is a simple meal but tastes great. Later we learned that different regions and cities in Morocco make their own versions, which means they season differently. We have often been asked which spices are used in the tajine we are served. The answer is always elusive and flawed. There are deep secrets in Moroccan cuisine.

Chefchaouen – the blue city

Morning dawned as we heard the Muezzin's call to prayer over Tangier. It was not difficult to find the motivation to leave the miserable hotel room and set off in the fresh morning, on the bikes.

The first target was Chefchaouen. Reportedly an incredibly charming small town, beautifully located on a hillside in the Rif Mountains, and where the Medina is completely blue.

After a few hours on a relatively boring little road, we had the same feeling as driving in Ølstykke in the rain, and we agreed to take a shortcut to get out on the main road, and that way faster away from Tangier's crowded outskirts, and closer to small cozy mountain towns. We thought it was a good decision, until half an hour later, when we were completely stuck in mud on a "dirt road". Let it be a lesson that when an incredible amount of pottery is sold on the side of the road in an area, you must stay off the dirt roads after rain.

Still, we reached Chefchaouen just as darkness fell. In the glow of the city's outermost street lamp, we googled accommodation options. Definitely an exercise we should put more effort into, we had to admit. We booked a room in a small guesthouse, in the middle of the blue medina. Perhaps not the most charming of them, but on the other hand one of the cheapest. And so began an otherwise evening filled with odd incidents.

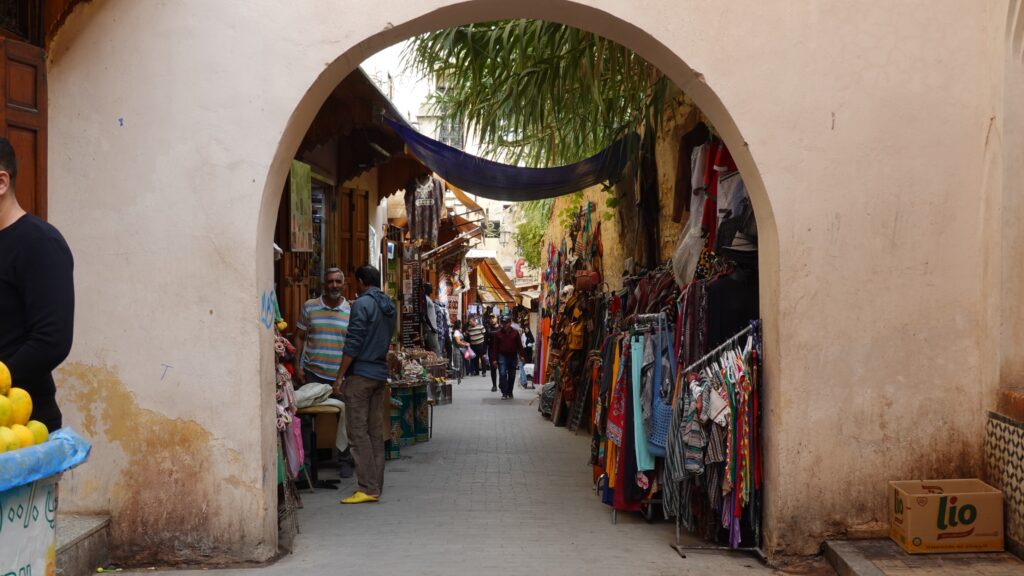

We entered the address on the map and cycled towards the medina. A Medina is essentially the old town. In other words, it is a jumble of small, narrow streets, around closed facades. Many of the elusive little doors you pass are hidden in large courtyards with nice, cozy houses, but until you enter such a place, you try to navigate up and down stairs, narrow streets and shortcuts, with a GPS that doesn't can get signal.

With Kenneth as an old surveyor, we arrived relatively quickly at the hotel's location, which in the real world was a completely empty square. You don't have to stand still and look bewildered for 2 seconds in a medina before you are offered help to get there. Either to the hotel you have booked, or to the hotel they would like to sell. In this case, however, everyone shook their heads when we mentioned the name "Casa Malek". Only when we tried to search on google maps, rather than Maps.me, it turned out that Casa Malek was at the other end of the city. But even when we got here there was no Casa Malek. Again locals volunteered and a guy was picked up from a cafe to show us the way, through dark streets, further and further away from where Casa Malek was indicated on the map. When the guy turned down a pitch black alley, we stopped and started turning the bikes around. But another guy came out of the alley and said, “I'm Malek. Welcome”. In addition to the slightly convoluted introduction, the house and the subsequent meeting with Malek were not as impressive as we had dreamed. But some will probably think that you get what you pay for.

Things went completely wrong the next morning when Malek presented us with an extra bill of 20% of the price, which he could not really account for. Kenneth became furious and we slammed the door without paying the extra bill.

Already on the second day in Morocco, Malek put a heavy yoke on our shoulders, which we struggle to shake off every day. Namely, a lack of trust that people want us well. The belief that there are no ulterior motives when people want to help us. Every day in Morocco has offered experiences that pull us towards each pole. One moment children are throwing stones at us as we cycle past, the next we are greeted by warm smiles and voices saying "Welcome". People on the street start a curious conversation with us about who we are, which ends in what they want to sell us. Many want to take us to different places. We have become good at standing still. But that goes against our curious soul. And what if we say no to a good experience, out of distrust for a fellow human being. After all, we also experience good things. The elderly man who comes out of his house when we have stopped for 2 minutes on the side of the road to take a sip of water and a snack. Luckily he speaks Spanish and encourages us to stay a bit. Rest. Sit in the shade. We can always drive on later, he says. He's not in a hurry. We feel a little embarrassed that we have, as we decline and pedal on.

The language is another challenge we have to deal with on a daily basis.

The two official languages in Morocco are Moroccan/Arabic and Tamazight (Berber language). In addition, French is taught, which we also do not know. In some places, people know a little English or Spanish. We wish we had taken a French course from home. It is daily frustrating for us that we cannot understand or say even the most basic things. Although not everyone here can speak French, there is usually someone nearby who does. Especially in a country where you are constantly accosted by virtually all people we walk or cycle past, it is a pity not to understand their intention or question.

However, we are completely clear that the children's questions are usually about money or sweets. Also to an extent that it has spawned a recurring conversation between us. Because can it really be appropriate that 90% of all Morocco's children has become acquainted with thoughtless tourists who have given the children sweets and money? Which is the immediate explanation for so many children running after us and begging. Today a boy came up to Kenneth and spoke perfect English, which is a rarity. He was a funny guy and asked why we had such strange bikes? If we had bombs in our bags? Kenneth replied: “No. It's guns!”. “Aaaarrrhhh” he said “Give me some money. I am poor". Kenneth burst into mild laughter and said: “You're not a poor man. You wear a Nike sweatshirt and nice shoes. Watch me. I only have this on the bike”. He replied: “You have more than that. You also have pistols”. He pointed to the bags with a smile. Then we told him that we are going to South Africa on the bikes, and everything about money was long forgotten. But he is a humorous example of how easy it is to say no. Less can also do it, a "No" is often enough. But what is interesting to us is why the children of an entire country, high and low, ask tourists for sweets and money. It is of course a possibility that the tourists themselves have "educated" the children so that there is something to pick up, even if we think it is reprehensible. But perhaps there is another deeper culture behind it? This is what we debate on the long stretches in the saddle. Because what if it's something more rooted?

If you go into a shop and want to buy a rug in Morocco, it is said to be a lengthy process involving long negotiations and numerous amounts of tea. Maybe even over several visits. Often the carpet owner will also start by asking what gift the customer has brought for him. As if to ease his mind leading up to the price negotiation?

In the very old days when the camel caravans crossed the Sahara with goods on the major trade routes, it is also easy to imagine that gifts must have been given to break the ice where you arrived.

More modern adventurers often tell of how they take gifts with them when they travel to visit isolated tribes in distant lands. Why?

…and is it really something of the culture that in some mysterious way still lives in a child's soul in Morocco, when you spot a cyclist in the distance and start a quick sprint in bare feet, across the sandy earth while shouting: “Bonjour! What do you have for me?”

This is pure guesswork and speculation on our part. Maybe there is a grain of truth in that. But in any case, the mind had something to occupy itself with in the blazing sun on the bike.

We also experience another, quieter, outstretched hand. An outstretched hand that touches us deeply and most often makes us put a coin in the outstretched hand. When we shop, or sit in a restaurant and eat, sometimes an elderly woman, an elderly man, or a child comes. Without saying anything, they keep a little distance, but seek eye contact. These are people who have nothing. It's not a conclusion we make based on their clothes or anything they say. But we can see it in their eyes. There is a quiet desperation that tells of a daily struggle to make ends meet. We see Moroccans giving them meals, giving them money. Sometimes they get the remains of an uneaten meal. Every time we see gratitude in their eyes. Like the locals, we also give these people food or money. Because how can you be a human being if you don't help those who look you in the eye and have nothing?

Fez and the world's largest pedestrian street

We cycled from the tourist trap of Chefchaouen, with its blue Medina, to Fez. By the way, we tried to find out why the medina was blue. No one knew. The best bet was that it was to attract tourists, which fits very well with our sense of the amount of authenticity in the city.

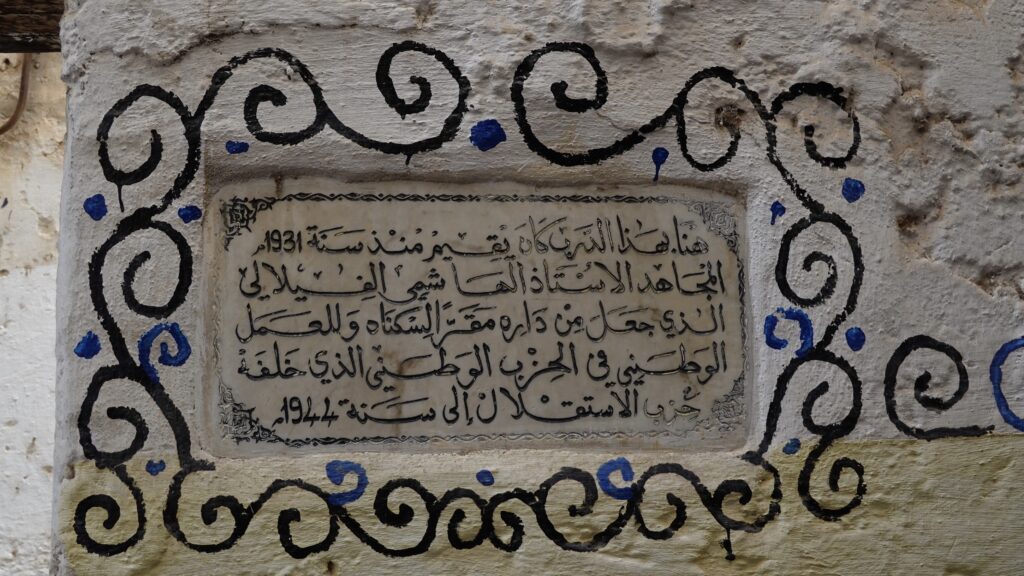

But there Fez stood in stark contrast with life and pulse. A large city with 1.5 million inhabitants, of which 150,000 live inside the medina. It is claimed to be the world's largest car-free urban area. There are 9000 small streets and alleys. Everything is convoluted and cryptic and a wonderful jumble of goods, people and food. The medina is divided into areas that trade or produce certain things. In one place they sell vegetables, in another they sell meat, in a third they sell modern bling. In some places, they specialize in working with metals and make, among other things, a. large copper pots, which they beat in beautiful patterns by hand.

They produce mosaics and fantastic food is prepared. The medina has several mosques with interesting stories, but they are not open to non-Muslims.

Instead, we spent half a day walking from one end of the medina to the other. Every meter was an experience in itself. Stealth glances through half-open doors revealed large courtyards behind. Congestion and tumult. And merchants everywhere. We ate our fill of sugary little cakes from a master baker in his Patisserie. We drank coffee in a café, next to a workshop where a man sat in a tailor's position with a small hammer, tapping patterns into tiles to make mosaics. In the end we found the winding road to one of the biggest attractions, namely where the leather is tanned and dyed.

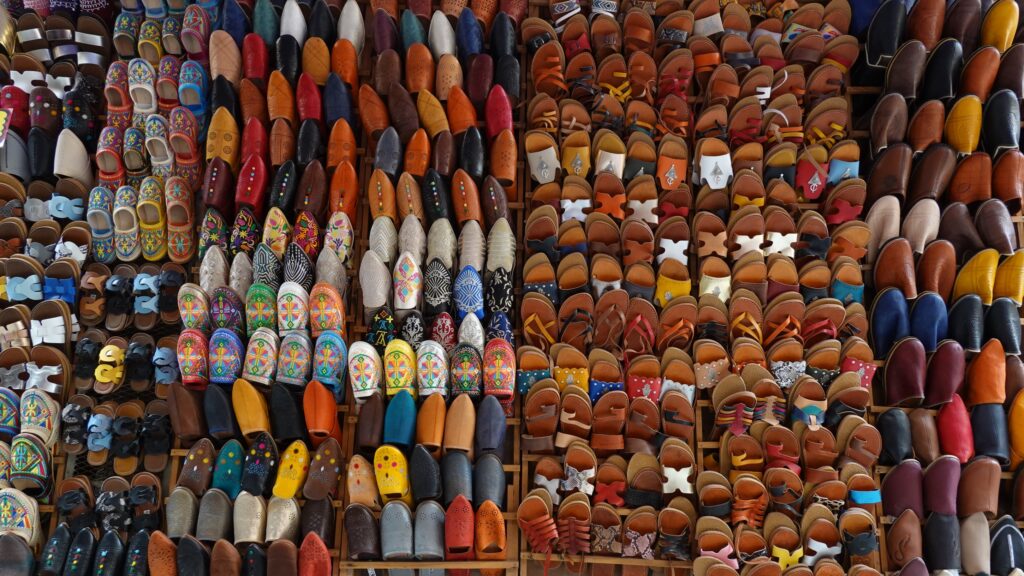

Let it be said right away, regardless of whether you come with a guide, or find around yourself as we did, you will not escape being dragged through the entire range of leather jackets, Moroccan pillows, sandals, bags etc etc before you finally find up to a roof terrace with a view over one of the large farms with the dye factories. But it is worth all the trouble and discussion. The catch is that all the roof terraces from which you can see the dyeworks are all associated with a leather merchant.

Every morning, new color is poured into huge vats, after which the skins are soaked in the colors. The rest of the day is spent with men walking around working the colors into the skins and hanging them to dry. It's all very sensual and in a way a beautiful scenario, but we're a little doubtful about how healthy the working environment really is. We hope for men's sake that it is under control.

From Fez we continued towards Imilchil, where we will follow a bikepacking route we have found on Bikepacking.com. We are very much looking forward to experiencing the landscapes down south in Morocco. We probably have to admit that we have taken the route planning in the northern part of the country too lightly. We have followed a few suggestions from others, in some cycling communities we follow. But to be honest, we have missed the unique experiences. The landscape of the Rif Mountains in northern Morocco didn't really blow our legs away. Not even though a large part of the world's cannabis is grown here, and the locals were happy to test the products. As they also generously offered us to do.

The humans didn't really take us by storm either. As we have tried to write, a sliver of mistrust often creeps into the relationships we enter into. Because there was often a reason for it.

Eg. there was a nice guy who stopped us on the road and asked if we needed help. We said everything was ok. He asked if we are on Whatsapp and we exchanged numbers. A few hours later he wrote again, now with google translate, if we were ok. And we thanked you for your care. After which the conversation turned to how we could help him come to Denmark and work. In a way, you can't blame him for that. But at the same time, it is a breach of the initial contract he made with us, that he offered us his help.

In reality, we believe that what we, with purely Danish eyes, would regard as a breach of trust, is more about a different cultural base. Just as previously described with the carpet trade, we believe that the natural way for a Moroccan to ask about something is along winding roads, like in a medina. That their language is much more full of poetry, or more flowery, as we would say in Danish. We clearly see that in the West we work hard to make it easier for the individual to manage everything himself, but here you can't even find your way in the medina without having to ask people for advice. In the same way, their interaction is perhaps more convoluted than our Danish, very straightforward and direct way?

We do not know. But we love to guess and question. Hopefully we'll meet someone we can ask.

Having said all this, we must also remember that we meet amazing people who invite us into their homes and lives out of a pure heart. Like the first time it happened, in southern Morocco. We have crossed the Anti Atlas mountains and are completely out of water. The temperature is 35 degrees. The first people we see are pumping water out of the hot desert sand, so we stop. While we fill the bottles with water, Rachid invites us home for tea. We meet his family and after washing our feet, we enter the guest room where they serve flatbread, olive oil, dates and Rachid pours sweet mint tea on high. Rachid knows a little English and we practice our French while we enjoy their pleasant company and fill our bodies with fluids and energy. When we leave, we hug each other and they give us the rest of the home-grown dates, which is a huge bagful.

We also have such experiences, and we let them occupy most of our minds.

Perhaps the experiences we get are just as much about how we deal with them ourselves. Perhaps we should also change our mindset from Europe to Africa.

Between the Anti Atlas and the High Atlas, a isthmus of desert enters between the two mountain ranges. Here lies the city of Goulmima. A small town that does not attract much attention from most travelers. But for us it obviously did because of its many bikes. There were thousands in the small town. Everyone cycled crosswise, women and children, young and old. Everyone had a bike. But it wasn't just the bikes that captured our curiosity. There was a special atmosphere here. People were more free. We had not seen women on bicycles before. Or women who approached us directly. People were relaxed and nice without being pushy. We wheeled down the small side streets and bought fruit from a wooden lorry, yogurt from a hole in the wall. Lunch at a plastic table in the shade at a cafe while a donkey walks by.

Here from Goulmima we turn off the main road, to once again set course for the High Atlas mountains. But we hesitated, because here in the warm center of the cozy city, we found something of what we had missed. A nice feeling of security that warmed our hearts.

But the mountains are calling. And the bikepacking route calls. In a few days we will hit the start of it, and then we will follow it almost to the border of the Western Sahara.

As we roll out of town, a friendly man stops us and chats. He proudly tells us that he is Berber, after which he says: "Welcome - to the REAL Morocco!".