Mauritania. A country we hadn't even heard of just a year ago. But after a month of warm smiles, men in blue suits, women on the backs of donkey carts, with iPhones in hand, traditional music, windswept desert landscapes, golden sunsets, raw and authentic living conditions, we have completely fallen in love with this desert country on the edge of the Sahara . It is not a country for the faint of heart, but for the adventurous who make an extra effort. In return, the reward is a thousandfold in experiences, surprises and warmth.

We were 4 cyclists waiting for the train in Nouadhibou. Gustavo from Mexico, Aymeric from Belgium, and the two of us from Denmark. Four souls who all had the same idea: To drive deep into the Mauritanian desert, with the 2.5 km long freight train, which transports 30-40,000 tons of iron ore from the mine in Zouérat to the port of Nouadhibou every day.

There is a daily departure at 2pm, and we were there exactly on time, knowing that we could end up waiting half a day or more. Because even though the train has a single passenger car, the priority is clearly mining, and therefore the train runs when it suits them.

Before we were even ready to jump on the freight train, we had a few days to prepare, in Mauritania's second largest city, Nouadhibou. The city is close to the border with Western Sahara. It was a huge contrast for us to arrive here, after almost 1,000km of cycling through the silent, desolate desert landscapes of the Western Sahara, where the wind was our companion and we only spoke to people when, on rare occasions, there was a kiosk in a small town.

When we arrived in Nouadhibou the noise from the car horns was infernal. On the other hand, there were no other electronics that worked on the smashed old Mercedes. Turn signals and brake lights should not be counted on. We soon discovered that the traffic was the Wild West, where whoever drives first wins the right of way. Often a donkey cart swerved directly into our lane, from a side road, and we had to slam on the brakes and pull the bike aside, between garbage and goats, to avoid a collision. But it was fun and intense. Even Gustavo from Mexico City found it chaotic to navigate around the people and old cars.

In Nouadhibou we stayed at Villa Maguela. A wonderful place a little outside the city, where especially the overlanders in their four-wheel drive like to pass by for a few days of relaxation.

We spent the time getting ready for the train ride, which we knew would be tough. About 12 hours in an empty freight car, under the open sky, with sand and iron dust flying everywhere, requires some "special equipment".

The days at Villa Maguela were well spent, because a sandstorm raged, so we couldn't cycle anywhere anyway. We checked the weather forecast and timed it so that we could take the train on the penultimate day of the sandstorm. So it was more or less fitting that when we had to get on the bikes again, the weather was better.

Tish, who works at Villa Maguela, had a box of discarded equipment from others who had made the trip. So without having to go to the market ourselves, we were equipped with ski goggles, old discarded jackets, sleeping bags, blankets and sleeping mats. We looked like something that was a lie, but that would prove to be paramount to an even fairly successful train ride.

At 6pm, after only 4 hours of waiting, the rails started to sing and the locals jumped off the track and got ready. We did the same. A gigantic diesel locomotive pulled the endlessly long train to us, and we could start loading our things. We allied ourselves with a couple of young backpackers so we could make a chain and it didn't take long to lift the bikes aboard the iron container that was to be our home for the night.

We managed to take a few pictures in the carriage, before the diesel engines kicked into gear again and with impressive power and a proper jolt, set the 2.5 km long train in motion.

The smiles were wide as we rolled out of Nouadhibou as the sun set. We thought of the train vagabonds of old and had romantic ideas about the impending journey through the Sahara and the night.

Shortly after leaving the city, we were already in the desolate desert. We tried to take some pictures, but the sandstorm whipped sand into the camera and destroyed the shutter. The camera had to stay in the pocket for the rest of the trip. Good thing, because night fell quickly. With the night came the cold.

We got ready on our sleeping pad. Marie with a sleeping bag, Kenneth with a warm blanket. What we hadn't calculated was that when the sandstorm rages, a blanket is not worth much, because the wind blows straight through. We ended up lying in a spoon all night trying to spread the sleeping bag over both of us, while we had to shout through the wind and the noise of the train when we had to turn over. We chattered our teeth from the cold while trying to get a decent position on the hard iron floor. The romantic thoughts of the trip were displaced by thoughts of how to position ourselves so that we wouldn't be thrown headfirst off the iron wall if the train slowed down hard. Kenneth had got some slightly worn ski goggles, where the sand whistled straight into his eyes, so only at night did he take his neckerchief and put it inside the ski mask, so that he could not see a stick, but on the other hand avoided sand in his eyes.

The first time the train stopped, we thought we were going to die. An ear-splitting sound, like a lightning train coming screaming towards us, signaled that all the carriages in the long line of trains were banging against each other, and we were just about to get ready when our own carriage slammed into the one in front with a huge bang, then we took off 10cm from the iron floor. It happened more than once that night. Let's just say that we didn't get much sleep and were probably a bit beat up when the next morning, after a 13-hour train adventure and 490km through the desert, we got off in the small village of Choum. We crawled out of our dung-stained clothes, brushed sand out of our hair, ears, bikes and bags.

From here we were happy to continue on our beloved bikes, which miraculously survived the night's wild train journey in the sandstorm.

This is how our time in Mauritania started and it could hardly be more adventurous. From Choum we cycled to the small town of Atar. The landscape was already raw and beautiful, now that we were really in the Sahara. But even though we thought the Sahara is a big sandbox, it turned out that the desert is so much more than that. Yes, in fact, only 20% of the Sahara's area is covered by sand. And only 9% of definite sand dunes, like those we know from the classic Sahara pictures. On the other hand, the Sahara is the size of the United States, so the 20% sand is still something.

Mauritania is only a small corner of the Sahara. Here from Atar, in the middle of the country, there was approx. 550 km of asphalt road back to the coast. The same distance is there to the border with Mali. But here there are virtually no roads or cities, just desert.

While the temperature slowly approached 40 degrees during the day, and the sand gnawed at the bikes, destroyed our zippers and crunched between our teeth when we ate, Christmas Eve also approached. We agreed with Aymeric and Gustavo to spend Christmas together. In Atar we found Bab Sahara, another cozy place where the overlanders stay, and we stayed here over Christmas. On Little Christmas Eve, the neighbor came pulling a goat into the square, between tents and parked four-wheelers. He exchanged a few words with the owner Just, and we understood that the next time we saw the goat, it would be served on our Christmas plate.

Atar was a nice town to spend a few days in. Much smaller than Nouadhibou, but just as lively. We were often at the market and bought fruit and vegetables, as well as bread. Or at the city's sidewalk restaurant to get a quarter of a chicken with fries as a change to the simple food we cyclists can cook on our stove. We also found camel milk for our oatmeal, and small deep-fried buns that look a bit like apple slices. A really good and calorie-rich snack. Otherwise, we have mostly lived on rice and canned sardines for dinner. There is not much fresh food on the shelves at the grocery store, as most of it is imported and has to be shipped out into the desert. Only 0.5% of Mauritania's area is cultivated as agriculture, which only covers about 30% of the need, in a profitable year.

It's always fun to sniff around the city's market. People are generally nice and welcoming and it takes a long time to do a few things because many people wanted to say hello and talk. In that way, it's very good that we don't know French or Arabic, because then we would still be standing there talking.

On Christmas Day we split up with the other cyclists. We went on alone towards Chinguetti, a small village which has small private libraries where ancient Arabic writings have been handed down and preserved for many generations.

The road there took us further into the Sahara, and we drove long stretches of excruciating washboard on the dirt road. At the same time, the bikes were loaded with a lot of water because there are no towns before Chinguetti. Therefore, Kenneth was very happy to accept a liter of water from a nice driver who stopped.

“The water is from Nouakchott, the capital!”

He said with a big smile before driving on. That same evening, Kenneth had stomach cramps and the trip's third sick day due to water was in the making.

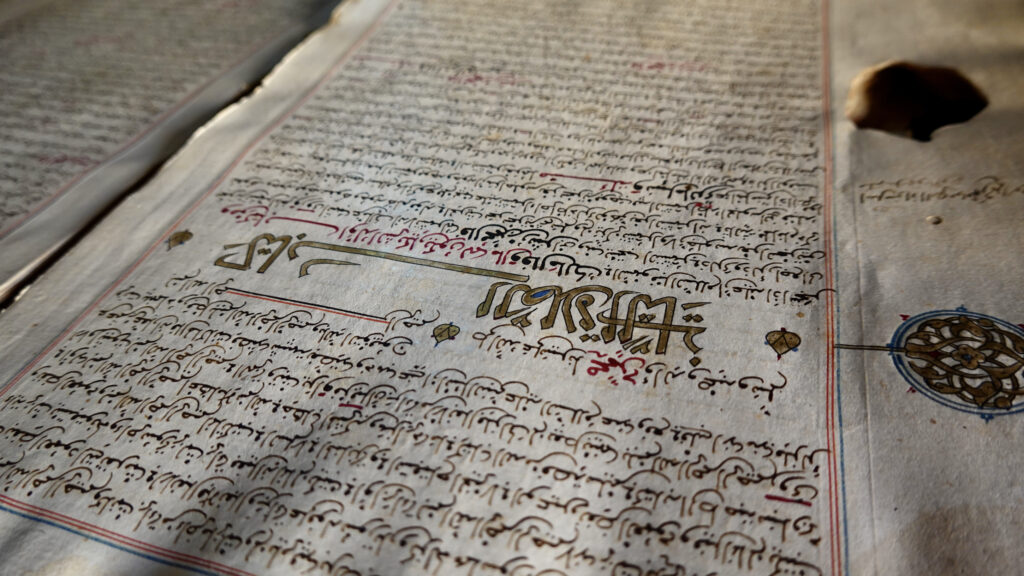

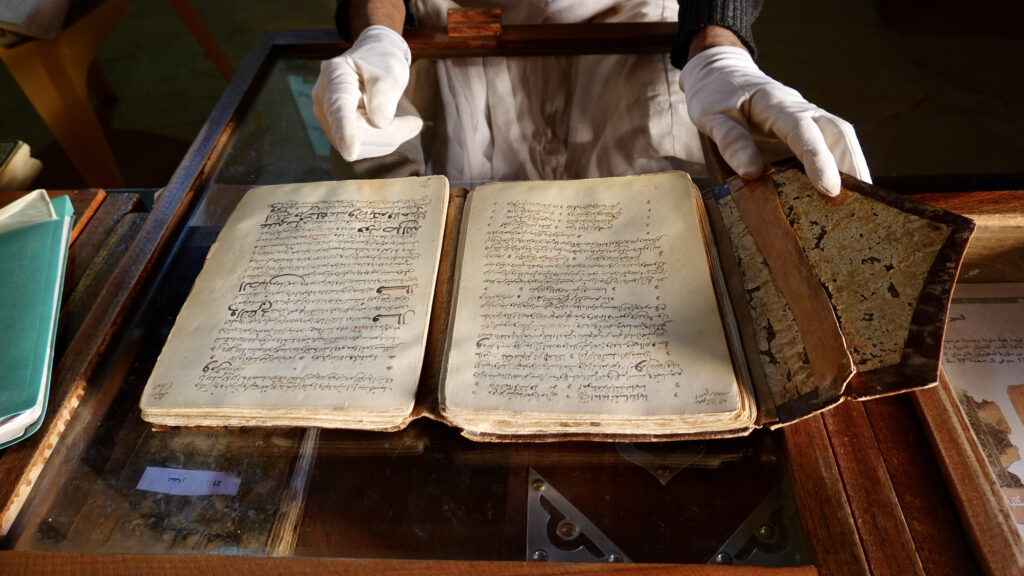

The next day there was only enough strength to see the beautiful old writings. We walked through the city where all the roads are sand so we couldn't cycle. An elderly man let us into the family library. With white gloves, he reverently took out one book after another and showed us interpretations of the Koran, mathematics, poetry, written by hand, on goat skin, several hundred years ago. It was super beautiful and exciting. Even though the whole city almost revolves around this tourist attraction, it was totally worth it.

For the rest of the day, Kenneth curled up in the fetal position at home in the small Auberge.

As Kenneth regained his strength, old longings came to the fore. Just as the train ride was one of the few things we knew about Mauritania from home, there was also another thing that beckoned. Even further out along the bumpy, sandy, difficult dirt road, lies Oudane. A village on the edge of the desert. In Oudane the road stops and you can't drive any further. Unless you have a four wheel drive and know how to behave in the desert sand. 50km outside Oudane is the Richat Structure. A geological phenomenon so large that it was only discovered when it was photographed from space. It looks like a giant meteor crater, 40km in diameter. But in reality it is a kind of volcanic explosion, where the entire earth's crust has lifted, to finally shoot off the 'plug', which again landed and closed the volcano. You probably think so. Because the fact is that no one knows exactly what happened 100 million years ago when the Richat Structure was formed. What we do know, however, is that it was one of the first to be included in the list of the 100 most amazing geological phenomena on earth. A list that can best be compared to the UNESCO World Heritage List.

Oudane itself, the small village, is also on the Unesco world heritage list, because of their beautifully restored ksar, which is the old town. The city was one of the important hubs for the camel caravans that traveled across the Sahara in ancient times, carrying goods between north and south. We got a super good guided tour of the old ksar.

But our heart was burning to see Richat Structure.

After the strenuous bike ride, 2 more days out on the sandy road to Oudane, we stayed at Zaida's. She is a woman with a big smile and a bone in her nose. We immediately felt comfortable in her company and asked her for advice on arranging a guided trip into the desert to see Richat. Over a cup of tea, we negotiated a price with her and waited for the guide with the four-wheel drive. When the tea was drunk, Zaida asked if we were ready. We answered yes. And then Zaida jumped in her own car and waved us in. We had not understood that it was she herself who was responsible for the trip. But we couldn't have asked for a better guide and driver. With Mauritanian music on the radio, and Zaida behind the wheel, we plowed through the desert sand at full speed and low tire pressure. It obviously requires good qualities as a driver to read the desert landscape, handle the four-wheel drive, adjust the speed and avoid getting stuck in the deep soft sand. Zaida mastered it all to perfection, at the same time smiling widely and singing along to the beautiful songs on the radio. We could hardly contain ourselves from sheer excitement. The drive alone into the desert, a place we couldn't possibly cycle, was a huge experience.

After an hour's drive we stopped and could now see the first outlines of the gigantic Richat. When you stand on land, it is difficult to understand the scale. You see a 40m high hill of sand and stone, but you can't see that the outermost ring curves. We drove through the outermost ring, and could now sense that the next ring, which is smaller in diameter, was bending. We drove over it, and could see the third and last ring from the top. In the center of the entire gigantic work, we drove up to the top and parked the car. We stepped out into the beautiful evening light and a completely enchanting view. It was a completely unreal feeling to stand right here in the center of such a special place without being able to fully understand what exactly had happened. All around us were huge stones, which on closer inspection were clumps of smaller stones pressed together. You can hardly imagine the forces needed to press stones together into a mass that most resembled nougat.

A truly magical place - BUT, you have to google the place to see a satellite photo. Otherwise it is impossible to understand the greatness!!!

On the way back through the desert, Zaida made one last stop at a large sand dune, where we could take some photographs in the last golden light of the sun, while she brewed evening tea over a fire in the desert sand. A beautiful end to a thoroughly fantastic experience.

Most cycle via Atar back to the capital Nouakchott, with a tailwind on tarmac. But we had seen the chance to spend even longer in the desert, by driving towards Tidjikja in southern Mauritania. A fairly desolate route with lots of desert wind.

There are quite a few villages on the way. Two of the most charming and memorable are M'hareth and the small oasis of Terjit. It is places like this that we must remember to close our eyes, try to forget that what we see has already become everyday for us, and then open our eyes again.

Children play in the sandy main street, between goats and chickens. Huts built in palm branches. Tiny houses built in clay. A donkey cart with a young boy beating the donkey with a stick as he drives large chunks of raw meat down to the sales stall. An oasis with running water and shade from the palm crowns, in the middle of the dry desert.

But also the modern contrasts, where young people have mobile phones and cannot detach themselves from TikTok.

About 10-15 families live in Terjit. It's completely quiet here. There are no modern machines that make noise. The cars are parked on the outskirts of the city.

M'hareth lies by a dried-up river, where bare-toed boys play soccer. We live in a cabin with Ahmedkori, who spoils us with lots of dates and nuts. We take pictures of him in his fine blue suit, and his kitchen as it now looks.

The scenery is fantastic on the deserted route. It is difficult to describe the beautiful rawness of the desert. The sunsets are absolutely stunning. The golden light wraps beautifully over the sand and our little tent in the desolate desert. When the day dawns, we can again see the endless distances in nothingness. When there is little vegetation, it always stands as a beautiful green contrast to the red sand. When there are rocks, they rise dramatically from the flat sand. It is so infinitely beautiful.

But it is also such a harsh landscape that it is difficult to understand how people survived out here in the old days. The sand penetrates everywhere. There is no water here, except in the few oases which lie at great intervals. And here there is almost nothing edible, which means that people have largely only lived on their livestock. But the nomads, of whom there are still a few left, have refined their survival methods over the centuries.

For us it was about planning our route so that we had enough food and water between the very few towns there are. Water in particular is critical now that the temperature has reached 45 degrees. We hate buying water in plastic bottles because we can see where that plastic ends up. There are no systems for handling garbage here. There are no trash cans here. Everything is thrown into the desert. This means that outside every small town, there are heaps of plastic and rubbish, destroying the fragile nature. It is a huge hope for us that a system can be implemented to handle garbage in Africa, because we guess the problem will not get smaller in the near future.

But until then, we would like to avoid buying bottled water. So when in Aujeft, after a few days in the desert, we were offered water from the well, instead of buying water, we said yes. And BAM, Kenneth got sick again. Lesson learned now. There are bacteria in the water that we are not used to. Marie didn't manage to drink the water, so she let go again. We have now ordered good water filters so that we can drink the water that the locals drink and not have to buy bottles of water.

Another problem with the rubbish, apart from the fact that it takes 50 years for a plastic bottle to break down, is that the animals also cannot distinguish between good and bad rubbish. In most places, the animals eat food waste, which is a good thing. But they also eat cardboard boxes, plastic, old shoes and whatever else they can find in the dumps outside the city, or even in the city streets. The goats, who eat the most, are ahead of us in the food chain, so all that rubbish is transformed into humans via milk and meat. We don't know what that actually means, but doubt it's a good thing.

Actually, there are enough problems to describe in Mauritania. It is a country with great natural resources, but a very poor population. It is seen in many places in Africa. Extensive corruption and a lack of creditworthiness quickly put an end to the fact that the economy that clings to natural resources benefits the people. We have cycled through villages where people live in huts built from clay and dried palm branches, and relief organizations have extensive projects here, yet there is great prosperity for some people in the big city. There is a lack of a sensible distribution of the goods in the country, which is one of the world's poorest countries.

Another problem many will cling to is that Mauritania still has slaves. Slavery was effectively outlawed in 1981, but still exists. Some sources estimate that as many as 10-20% of the population actually live as slaves. The reality is, as often, a bit more nuanced. Slavery can perhaps to some extent be compared to the caste system, in that one is born into a certain social class in society. The reality for many slaves is that even if they are freed, they have very little opportunity to change their lives. They cannot necessarily get a job. They cannot move out of their social class.

Mauritania is located in the borderland between Arab North Africa and black West Africa, and you can clearly see that there is a ruling class consisting of Arab descent, and a working class consisting of blacks. It is obviously set up a bit squarely, but it is the reality both at government level and clearly in the everyday picture.

But, as we have experienced in so many other places in the world, kindness and hospitality are not dependent on one's economic prosperity or social status.

After spending some amazing days in the beautiful desert, we approached southern Mauritania. In the dusty town of Sangrave we drove, as always, straight to the grocery store with the biggest fridge. As we helped ourselves to cold water, coke and yogurt, a guy addressed us in English. It's the first time in a long time that someone has been able to speak anything other than French and Arabic, so we quickly fell into conversation. The guy was talkative and we were a bit suspicious of his intentions, but he kept inviting us home and said: "It will be a good experience for you, which you can remember when you get home". And he was right about that. As our cycling friend Aymeric says: "You have to see with the heart" and with the heart we could see that Mafugi was good enough, so we went home with him.

He just wanted to make us a quick lunch "now-now", then we could drive on. It was almost three in the afternoon. It gets dark at 7pm so we thought it was fine.

At home, the gas stove didn't work, so the food ran out, and it ended up that lunch turned into a late dinner instead. In the meantime, we had pitched the tent in his garden and enjoyed being able to talk to him about life in Mauritania. He himself was from Gambia, but has worked here for 7 years. When Mafugi talked about The Gambia, his eyes lit up. When he talked about his wife, about the food, about The Gambia being the land of smiles in Africa, he made us look forward to starting a new chapter in Africa. When we soon roll over the border into Senegal, we know that the upheaval will be great. We are leaving the Arab world. We arrive in black Africa. We hardly know what that means yet, but we can feel positive currents brought to us from Senegal.

Mafugi said he had to be at work at 8 the next morning, so we set the alarm for 7. But the house was quiet. When we poked our heads inside, he and his colleagues were sleeping on the floor in the small room. They slowly got eyes. His colleagues immediately went to work, but Mafugi stayed and made breakfast for us. Gambian coffee, as he called it. A large bowl of hot water, 3 leaves of Nescafé, 2 leaves of tea, a large handful of sugar, 2 cans of condensed milk. Such! A power drink to start the day. We were each given a half liter drinking cup to start the day.

We thanked Mafugi for his warmth and hospitality before heading out into Sangrave's morning jumble of goats, people, buses and trucks. But with big smiles on their faces.

Now we are in Aleg. A town close to the border with Senegal. Here we have found a small hotel for DKK 140 per day. We are almost out of the desert so we have cleaned and serviced all our gear. It really needed it. The bikes are sparkling, the tent is washed and we clean up mentally.

Mauritania has been full of fantastic experiences. We had no idea what to expect. But the raw nature, the authentic everyday life, and the many nice people have made Mauritania a country that we want to return to and experience more of.

We don't see many tourists here. Only people who want to drive 4x4s in the desert, and quite a few cyclists who, like ourselves, are heading south. Why aren't there more tourists here, one might ask? Perhaps precisely because it is raw here. There is no luxury here. You have to be willing to make an effort yourself to travel here. But there may also be something else at play.

In 2007 in Aleg, the town we are in now, a French family of 5 was shot down. Only one survived. The story among the travelers we meet is that some locals had seen the family withdrawing money, followed them to rob them, but ended up shooting them. In other words, a robbery which developed disastrously.

The international media, and Mauritanian ditto, write that it was a dormant terrorist cell, or at least that several of the killers were trained by Al Qaida. Three of the murderers have been sentenced to death.

We do not know which is more correct. Probably both. But the consequence for Mauritania was that Paris-Dakar changed the route and the foreign ministries of Western countries have colored the majority of Mauritania red. 15 years later, travel guides are still marked by this incident.

It is not up to us to advise on travel for others. But we can state that we have met fantastic people in this country. We never felt exposed. We feel that people are honest and treat us well, and that people are basically helpful without being pushy. As always, we have the very best experiences outside the obvious tourist areas.

We hope for the people who live here that they will experience sustainable progress.

The hotel we are staying at now is run by two brothers. Last night they invited us to a tea ceremony under the tent cloth in the front garden. As they said: “Mauritanian tea takes a long time to make because in the old days there was nothing else to make. You couldn't read, you couldn't watch television, you could only talk and make tea”.

As we sat in the balmy evening, drinking one shot glass after another of frothy sweet tea, the two brothers said: “Our parents were born and raised in the desert. They lived a hard life. But we grew up and studied in the capital. We want to live the modern life. It is easier and more comfortable”.

◦