Togo and Benin are largely about the ancient religion of voodoo, which is practiced here.

But also about extremely nice people. About getting my shoulders down a bit again and finding my way back to the cool places to cycle and the good experiences in the small villages, out in the countryside.

On the other hand, it was unlikely to be difficult to enter the countries. Let's start the narrative there.

No. No. No!!!

No matter how much I tried to argue with the border guard, I really knew from the first second that the battle was lost, that I was not allowed to cross the border, to enter Togo.

I had exchanged all my money and emptied my phone of credit. It would be annoyingly difficult to start over.

But there was also another reason why I had difficulty accepting the rejection; i was SO ready to leave Ghana. The experiences in "Africa for beginners" had leaned surprisingly much to the negative side, and when I rolled up to the border barrier a little while ago, I almost cried with happiness at being able to put Ghana behind me and start a new chapter.

Now the rejection was almost unbearable mentally.

But in practical terms it was also a bit confusing, because all my research pointed to me simply asking for a 7-day transit visa at the border with Togo. And that was exactly what they refused with such arrogance that I was about to explode from impotence. Completely soaked, in rain gear from head to toe, I shuffled back to my bike, hopped on it and pointed the muzzle towards a border crossing 30km further north. My thought at the moment was that I must be able to get the visa up there. That they would be easier to talk to, further away from the big city.

While I was cycling, my whole head was buzzing. Not only from a strange headache that had begun to creep up on me, but also from what the perspectives were. I had 10 more days to be in Lagos. There I was to meet Marie at the airport when she came back from Denmark. The border police told me that all visa applications must now be done online. And I found out that the earliest application date was 5 days ahead. But that the application process itself could take 7 days. That would force me to race straight through Togo and Benin to Lagos. It smelled far too much of what we had just done in Ghana and the Ivory Coast, and lying on flat asphalt for several days in a row had been absolutely no adventure.

I missed the adventure. The experiences. Time with the locals. Everything I had come to Africa for. I could feel a mental fatigue. Maybe it was the frustration over Ghana's completely brain-dead and life-threatening traffic, maybe it was just time to pull your head back into the turtle shell and let the experiences sink in a little, without being on all the time. Or maybe it was frustration at being on such a big adventure, without feeling that tickle in your body out on the tarmac.

Long road to visa

When I reached the next border post, I smeared my entire corpus into boyish charm. With my biggest smile and a twinkle in my eye, I walked up to the border barrier. After a little talk, I was allowed by the guards to try my hand at the boss. But the guards immediately believed that the message was the same.

I braced myself even more and added an appropriate amount of reverent respectability when I met the man in uniform. With extremely well-chosen words and a crushing calm, I presented my case. He was cold as a snowman! But I didn't give up. Tried all possible argumentation techniques, suggested that I could pay "a fee" for the service (which I am otherwise totally against). Nothing helped. The Ghanaian authorities entered the field and, quite unexpectedly, threw themselves into the fray, on my side. They explained up walls and down posts about my situation. I said if that would solve the situation, I could cross Togo in 5 hours (yes – that's how small the country is). Eventually, I lost track of who was who and who set up who to influence whom. But after more than an hour and a half back and forth, I stood again in front of the snowman, who had only become even colder. He ended up telling me directly that now I should get on my bike and ride back to Ghana, after which he took a motorbike and accompanied me down to the gate where he instructed people that I should leave the border area.

Then I was back in Ghana. Nothing had changed in my situation, except that I had wasted half a day. But I did get one thing out of it all, because one of the Ghanaians mentioned that they had a Chinese a week ago who was in the same situation: "He had to go back to Accra and get the visa done there".

I exchanged my money back to Ghanaian cedis, topped up my phone with credit and found a dingy hotel and spent the rest of the evening googling. It was good enough. Instead of applying for the visa online, it should be possible to go to the embassy in Accra to get it done. A huge chance not to wait for the online application. My hostess at the hotel confirmed that there are buses from the border to Accra. If all went well, I could get a visa tomorrow and cross the border the day after tomorrow. I fell asleep with my fingers crossed.

After a 4-hour near-death experience in a bus with a 25-year-old who has seen too much Formula 1, behind the wheel of the completely smashed Ford Transit, we had covered the 150km back to the capital. The smile was spread wide again when I entered the embassy. It worked. The lady behind the counter smiled back and asked me to fill out some paperwork. It boded well.

A few hours later, the mood had turned 180 degrees. They were not happy that I had specified "landscape surveyor" as a job. I had pulled my old title out of the hat so they wouldn't think I was a journalist from TV. But now I think I had set myself up, because "surveyor" might be confused with an observer. Presidential elections are imminent in Togo, and they tend not to be terribly interested in being scrutinized too much by international observers. But it worked. I got my passport with visa and was able to head back towards the border. 7 hair-raising hours later, I finally reached my hotel room. Pyyyhhh I'm glad we usually cycle ourselves.

Togo or not to go

The next day at the border post I appeared somewhat more confident, passport triumphantly in hand. But they weren't that impressive. There were strict orders to call the top commander to get my entry into Togo approved. It dragged on. The guards smiled slyly and said, “It's no problem. Do not worry". Inside I cooked. But after a while the guard's phone rang and I heard a positive statement.

Then one would think that it was a formality to be stamped out of Ghana, now that I had finally been allowed to enter Togo. But it was like swimming in wet concrete. Now the Ghanaian boss "wanted to talk to me", so I was dragged into the office to be schooled. The man who had followed me to the boss just managed to whisper: "You have overstayed your visa in Ghana, that's why you need to talk to the boss", before he left the office. I dropped my jaw but tried to think fast. It couldn't fit and I thought they were out for money. I was told to sit down and wait, but instead walked across the room to the boss, gave him a firm handshake, looked him kindly in the eye and asked, "What's the problem?" He was standing with my passport in his hand and I could see the dates on the stamp. I had a 3 month visa and had only been in Ghana for 13 days. For the next few seconds, time stood still. I awaited his words. What was his intention? Did he want money? But I could see in his eyes when he looked at the passport that he realized they had made a mistake. He looked at me embarrassed, gave an order to his soldier and immediately left the room. 1 minute later I was stamped out of Ghana.

It usually goes easily at the borders. There have been no problems so far. It can be more or less elaborate, slow, bureaucratic affairs, but it always goes by the book. And so far it did here as well. Exactly by the book. This time it was me who had been in Africa too long and heard too many robber stories, so I thought I could get around the rules if a little money came on the table. But it didn't work. Which is actually pretty cool.

Up until now, we have collectively spent more than DKK 20,000 on visas. It is a costly affair in West Africa. On the other hand, the troublesome and expensive ones of this kind should now also be in the house. We are missing Angola, Namibia and South Africa. We are not that nervous about them.

You can't love all… countries

As soon as I crossed the border, with my newly acquired visa, the mood changed. The traffic calmed down completely. People drove much slower. Considered each other. There was even a wide discount I could ride on. People smiled and nodded, instead of shouting at me. The shoulders slumped and the smile returned.

And NOW I was looking forward to experiencing Togo. I had lost some time, so I headed straight for the capital, Lome. The entrance to the center was the most peaceful I have experienced in a big city. Despite loudspeaker vans agitating for voting for the presidential election, it was relatively calm. I drove around a huge market and filled the bags with fruit. The woman I was shopping with called me “Mon ami”. An expression I had to hear again and again. Togo is French speaking, but everyone speaks fine English. Much better than in English speaking Ghana.

I so wanted to like Ghana. I always try to see the best in a place. To understand the reason for the state of affairs. To accept and even love the cultural differences. But our route through Ghana was marked by touristic areas where locals were fed up with whites and only tried to exploit them. At the same time, the traffic on the asphalt roads was directly dangerous. Several times we were both about to be run off the road, by young men who don't realize how dangerous they are driving.

When I landed here in relaxed Togo, it really dawned on me how bad an experience we had in Ghana. And I have to make peace with that. On the other hand, I am sure that if we had driven further north in the country, away from the tourists, out into the countryside, up into the mountains, we would probably have had lots of wonderful experiences.

Voodoo for all the money

What I was most looking forward to experiencing in both Togo and Benin was voodoo. The mythical religion that is so demonized for us, through American movies that breathe the fear of the dark side. Voodoo dolls with needles in their bodies, which are to be used to hurt another person. Evil spirits. Priests who can make zombies out of living people. Black magic. This is the image we know of voodoo. But my rational brain tells me that when voodoo is a state-recognised religion, which approx. 2 million of Benin's population practices daily, then there is probably not only death and destruction behind this mystery, which we really don't know much about.

In Lome is the Akodessawa fetish market. A market full of relics that are used when practicing voodoo. And souvenirs. Because even if someone claims that it is Togo's, even West Africa's, indeed almost the world's most significant voodoo market, the reality is that it is an obvious tourist attraction with a large sign indicating the entrance fee and the price for taking pictures.

I didn't mind giving a shilling to learn something about voodoo, but ended up in a friendly discussion with a boy who took a picture of me, whether he should also pay for it. I didn't manage to wring an ear out of him.

Included in the price I got a guide. A passionate guy from Benin, who on the one hand talked about the bright sides of voodoo, but on the other hand also touched on the possible dark sides, without wanting to answer any further questions about it.

What is voodoo?

Voodoo is a natural religion. Animism. The religion originates from the indigenous people who have lived here in the area for the past several thousand years; The Ewe people.

I can't claim to have gotten a clear and coherent explanation of what voodoo basically is. But I also think that it ties in very well with the nature of voodoo. That it is pretzel. Inaccessible. Incomplete. Inexplicable. There are no written rules or traditions of voodoo. Everything is oral and has traveled through generations and halfway around the world. Therefore, voodoo looks very different in different places of the world. But let me share some of what I learned anyway.

Voodoo comes from the Fon language where the word Vodun means god or spirit. There is a unifying or supreme god; Mawu. And including a lot of little gods for many different things. The gods work to do good things for the people, therefore the people take it upon themselves to give the gods food and drink. You could call it sacrifices. Typically goats, chickens, dogs and cats.

The voodoo priests act as mediators between the humans and the gods. So if you want to ask the gods for protection or help, you go to the priest who will tell you what to bring him, and then he will make a ritual to achieve what you want.

And here it gets a little unclear. Because now the person has been sent to the voodoo market, called the fetish market, to buy something specific. In the fetish market, there are so many dead animals in all sorts of different guises that you think it's a lie. But there are also live animals that can be bought for sacrifice. Just as you find amulets and the like. As well as voodoo dolls for the tourists.

How the ritual with a dead animal takes place, I never quite understood. The live animals are sacrificed, the blood poured on various voodoo relics and eaten afterwards.

There is much more to tell about voodoo, but let's pause at the fetish market. Because it's probably a wild place. I think I'll let some pictures speak for themselves.

NOTE: The pictures are not for the faint of heart!

Back in proper element

From Lome I drove out again on the small roads, out into the countryside. With the sound of crunching gravel under the deck and the sight of the Ewe people's neat fields of yams, corn and papaya, I tried to get far enough away that I could spend another night in the tent, which I miss.

At a small river I struck up a conversation with a local woman as we boarded a small wooden boat. On the boat trip across the river, the woman and the boatman talked about the local palm wine, which they were almost horrified that I hadn't tasted. The woman promptly invited me to her house so I could have a drink. Of course I said yes.

10 minutes later she pushed open the door to her patio and we stepped in to children and grandmothers who greeted us kindly. A chair was placed before me and a cup of water thrust into my hand. I like a lot the kindness and the forms that surround receiving strangers. You immediately feel welcome. The woman found the bottle with the palm wine and told how they knock a spigot into the tree, and drain the liquid, which then stands for a while - and something with something - and then it becomes palm wine. First, the woman drank a glass herself. Then one grandmother joined the field. And finally I got the small shot glass, filled to the brim with a good draft of palm wine, which burned in my chest. It actually tasted pretty good.

The woman then said: "Now you have had your palm wine, so now you can drive on to the market in Vogan, which you wanted to reach". And she was right about that. So just as quickly the invitation had landed in my lap, just as quickly I was out the door again. Now with a small sly smile on his face and light legs.

Up in Vogan, the town was indeed busy. It was market day and everything was cooking in a wonderful atmosphere. I was looking for a hotel room. The first place I asked, the owner looked very puzzled and exclaimed: "Do you want to sleep here?". Even then I should perhaps have just answered "No - not when you say it that way". But it wasn't until I saw the room that I pulled the feelers to me and looked further.

The next hotel was called the Better Hotel, which was very promising. Outside sat two women and a little boy. I asked if it was a hotel? They confirmed. Then I asked what it cost, but before they could give a price, they wanted to know if I wanted "cream or fun?". Without fully understanding what was what, I still got a little confused. I tried, without offending anyone, to explain that I just wanted to sleep. "Aaahhh - you want simple?". I took the chance and confirmed. "So no fun?". No thanks – we agreed on simple and the price seemed to fit with extra services being taken out of the accounts.

Everyday voodoo

The next day I drove a little further north, along the small dusty dirt roads. I found some nice singletrack that led through a forest, and completely outside the map's road network. But I had a good feeling of being able to find my way, on the sense of direction. Until I stood in the middle of a courtyard by a small cabin and 20 high-pitched young men fell silent for a split second, their jaws dropping. It also helped that I tried to ask for directions - they were completely speechless and speechless. A big mama with bare breasts stepped out the door and took control of things. She explained to me the way forward, while the men perked up and nodded and said yes yes.

When I reached a town again, after my singletrack shortcut through the woods, I found a kiosk selling hot soda. Not everyone in the world can afford a refrigerator.

I sat on the kiosk's porch and drank the hot sugar water.

Here was a table full of dead animals. I asked if it is voodoo. Some men nodded and I was allowed to take pictures. It always fascinates me the most when you get to the places where other tourists never go, so you can experience the culture purely. There were no entrance tickets or souvenirs here. No voodoo dolls. The most striking thing was that it was apparently a little girl of 10 who was selling the things. I would have liked to ask more about that, but she didn't speak English, and the men were a bit rude.

I finished my hot soda and jumped back on the bike.

The heat and headache increase

It's so disgustingly hot here. It's hard to drink enough because I don't see any wells and the kiosks are too far away. I should buy more water with it, but misjudge all the time. I have a pretty bad headache now. I think it's dehydration, but I'm also starting to think there's something else going on.

In addition to the heat, the humidity is about to knock me to the floor. I am watching news from Nigeria where the heat wave is a big topic.

Even the locals here seem to be affected. At least there are quite a few women who have taken the consequence and thrown away the shirt. Neopuritanism has not reached Togo.

I sweat 24 hours a day and am aware of dehydration but have a hard time solving it. At the same time, there are far between the food stalls and the portions are small, so I don't get enough energy either.

The epicenter of voodoo in Benin

After only 3 days in Togo, I cross the border into Benin. I am headed for Abomey, which was the seat of the Dahomey kingdom. That is, from before the colonists divided Africa with a ruler on a desk. In Abomey, I was immediately fascinated by the city's rich cultural history, which is very evident in the streetscape. Everywhere there are ornate house walls that tell stories about ancient times. Also on new buildings.

The city also has a large fetish market and is generally the epicenter of voodoo. I wanted to know a lot more about voodoo and had a thousand questions. I had been looking forward to coming here and researched a guide named Mark whom I contacted. Mark could not be reached in the evening. But the next morning he reported that he was ready for a tour. "I'll come and pick you up in 35 minutes". And of course I knew that was a lie. He had probably just gotten up. When he finally came, an hour and a half later, he looked somewhat stiff. I seriously don't think he had slept all night. But he had good recommendations from others and I was excited to experience something, so off we went. I jumped on the back of his motorcycle and we drove off to visit a voodoo priest first thing.

Visiting the voodoo priest

A little old man, who touched my chest and reminded me of Yoda from Star Wars, looked me kindly in the eyes and welcomed me. We took off our sandals and entered his house, in the first room where his voodoo altar was. He started speaking in the local language. Occasionally he would take a good swig of a palm wine and spit it out over his various voodoo figures. Then he took a calabash, made a rhythm with it, and began to mass. Mark translated most of it, which was about blessing us and asking the gods to protect us.

From there we went out into his courtyard, where a similar ritual was repeated. There was a very beautiful calm about the old man as he stood there in his bare toes pouring wine into small jars, stepping figures on their heads and messing on the phone. But there was also an absurdity in the fact that we were standing there, the three of us together in full sunshine, calling for the protection of the gods via clay figurines doused with palm wine.

In the last room were some of his oldest figures, which had been passed down in the family. They were all the way back from the seventeenth century. The priest showed me quite a few different amulets you could buy. I found a little bag of secret ingredients that you could keep in your pocket. He put it in my hand and sprinkled white powder on it. Then he asked the gods that it might protect me from evil on my way. Finally, I blew the powder off the amulet and closed my hand around it, pocketing it.

I thanked the priest for an insight into his voodoo and for letting me visit him.

Motorcycle guide

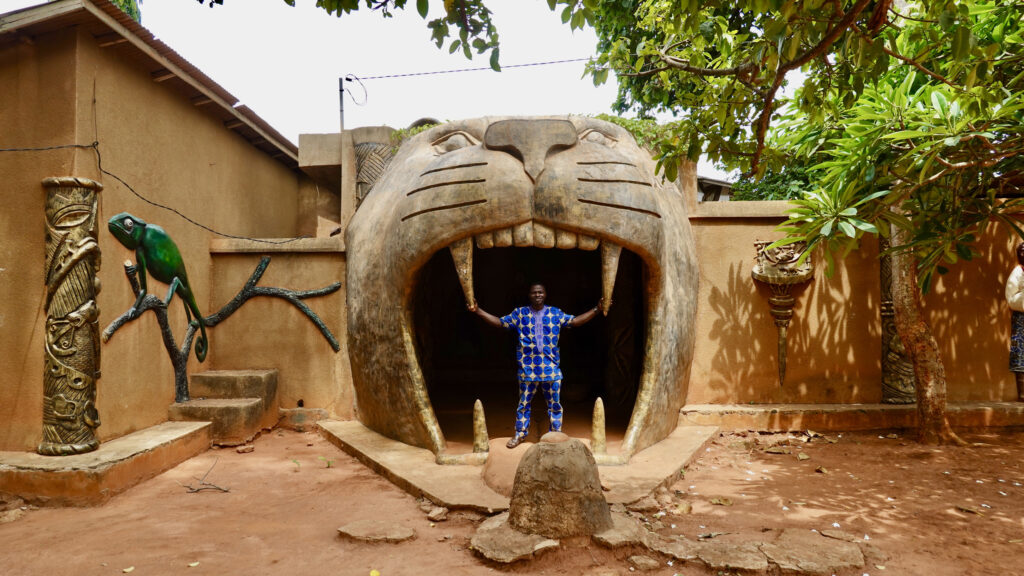

Throughout the day we rode around on Mark's motorbike and visited various places of importance for voodoo in the area; a church shaped like a giant chameleon, a fetish market, and a few of the palaces that the kings have inhabited. Throughout the trip, Mark poured out his knowledge.

Today's climax

But I didn't have the wildest experience until the evening. I had told Mark that I was interested in experiencing some of the rituals associated with voodoo. In January there is a huge festival where you can see the rituals and dances. But for the rest of the year, there are still a lot of things going on in the small villages. Mark talked to quite a few people during the day and finally managed to get word that Engungun was loose in a small village close by, that evening.

When Mark picked me up again, he was significantly healthier. Yes, almost energetic. And we were in a hurry to get off so we could see Engungun before it all stopped again. Primarily because he was again half an hour late for our appointment.

We milled through town and could see a crowd starting to gather. Mark seemed a little stressed as he parked the motorcycle. He ran up to some men and asked them something. Then he waved me along through a long alley. At the end we could see a shouting crowd, surging to and fro like a raging sea. A couple of times people came running towards us and Mark grabbed my wrist hard. He pulled us back. The people now ran back towards whatever was in front of us. We followed. But when suddenly a large number of young excited men came running towards us, Mark pulled me hard and shouted: "We can't be here". Together with the crowd we tried to get away, through the small alley. First we waved with the people, then we had to fight against the crowd as everyone else wanted to go back again. Out on the road again, Mark had to find that his sandal had been stepped on by him and had lost its strap. He seemed a little upset. But he got a good idea. There was a gate next to the alley. We went in there and by a wall a couple of benches were placed, with a lot of people on them, looking over the wall. We jumped up and had a look.

In front of us was a large open space, with a huge tree in the middle. The square was packed with young men. Everyone was a little excited. Many stood with their sandals in hand. Everyone was ready to run for their lives. Because suddenly a dangerous spirit came running, dancing, spinning into the middle of the crowd, with unpredictable movements. An Engungun was loose. If it touches you, you are dead, and must be carried away by your comrades. When Engungun comes, everyone flees, scared out of their wits. But of course some play with death, like a bullfighter trying to get close without getting hit. The mood was at the boiling point. People looked wild in the eyes. What might look a bit theatrical to a Western eye was serious. And so anyway. Because there were also relieved laughs and pats on the back for those who just avoided death.

Who is One gun?

When a person dies, the person will lie in their home for the first time. After a few days, the spirit of the deceased will appear in a mask, an Engungun, before leaving the family.

After a year, the spirit then returns, and it may want to bring a message from the deceased, which it wants to tell. Perhaps it will hunt down a certain person who hurt the deceased.

But it will also hunt the people who participate in the event and try to "kill" them.

Engungun is not a disguised human. You can see that from its shape. It has no human forms at all. For example, it has no face, it typically has many fluttering layers, maybe a completely square back and it might have a small head on its back.

If an Engungun stands in front of you and you give it some small money, you can get a blessing from it.

Only white man

Again, it was fantastic to experience how voodoo takes place concretely in everyday life and in the lives of ordinary people. This was not a tourist attraction. I was the only white person, along with maybe 200 locals. It was quite a wild and intense experience. And now I had ten thousand questions.

Does voodoo have a hidden side?

On the way home I asked Mark what it was we had experienced. He explained a little, but not as much as I could google. And that's probably the experience I'm generally left with. Those with whom I have spoken about voodoo would very much like to conjure up the image of black magic in the earth. But they find it difficult to give a clear picture of what voodoo is more precisely. And they consistently avoid answering questions about black magic, which they admit exists.

I understand that you want to get rid of the stereotypical attitude that comes from American movies. It is condescending to portray someone's religion so one-sidedly.

I understand that voodoo is something else. But there is a restraint. Something unsaid. Voodoo is not something you show off proudly. It is difficult to understand a whole. It seems like a lot is hidden.

As I cycle out of Abomey the next day, I stop and take a picture of an ornate wall. Something has caught my interest. Because something here is different from the nice picture I was presented with yesterday.

After I have taken the picture, two young men come running out and talk to me on the phone, in a somewhat intense atmosphere. I calmly tell them that I don't understand. "Not for tourists!". OK. I understand. Fair enough. One comes close to the bike and I can see he wants to open my bag where the camera is. But he gives up. He gestures for me to come inside. The other says in broken English: “Come inside. We don't want to talk to you”.

It will be a no, boys - and I drive on, but look over my shoulder just once...

Goodbye Togo – hello headache

I am aiming for Porto Novo, the capital of Benin. I am running out of time before I have to meet Marie in Lagos.

My head now hurts so badly that I have to visit a doctor's clinic, where I explain that my brain feels swollen. As if it cannot be inside the skull.

The doctor google-translates that he will give me a syringe and then he will take some tests. I ask what kind of syringe it is. "To make you feel better". I talk him into taking samples and finding out what's wrong before I get injections.

He finds nothing but the malaria that is still smoldering since Ghana. But we agree that it's time to knock it down. I don't want to keep straining the immune system.

However, I myself suspect that it is more dehydration and ask for electrolytes. They don't have that at the clinic. Not even at the pharmacy. Nowhere. It's getting critical.

I continue to Porto-Novo. Here I'm looking for the city's soul, but I can't really find it.

But the brain thinks too slowly. I'm concerned. There are no proper hospitals here. But in Lagos I know there are many expats who work for big companies. That is why there are several good hospitals. I decide to go there a day earlier than planned and put all plans aside until I have been to a proper hospital.

The next day I cross the border into Nigeria after less than 500km in Togo and Benin.

The two countries deserve much more attention and I would have loved to spend much more time here. The culture is wildly exciting. The people were really nice and welcoming. The traffic was exemplary – in an African context.

But we'll have to come back another time.